“Why should you care about player inclusivity?”

It’s a sentiment that’s repeated in board rooms, digital forums, and during industry dinners — why should anyone care about player diversity or representation in games? It’s a question that was on a number of minds within the development community at this year’s Game Developers Conference in San Francisco, which heralded 60 talks in their advocacy track. Tyler Hutchison, game director on Dream Daddy — a dad-dating simulator that quickly became the indie darling of 2017 — gave a talk about how Game Grumps created inclusivity without spending a ton of money.

“Well, it’s 2018,” Hutchison began, after asking the initial question. “Now that we’re all on the same page, we agree that player inclusivity is really important to have in your game. It probably makes for better games — no, it definitely makes for better games.”

Indie games are often first to the table with creative mechanics and narratives that AAA executives and producers would reel at, especially without data and a business case to sell the concept in question. In that way, Dream Daddy isn’t just a dad-dating simulator — it’s an excellent example of how indie game developers can embrace diversity without wandering down the path of overly complex (and budget-breaking) narrative mechanics.

Five years ago, during GDC 2013, Tom Abernathy — current narrative designer at ArenaNet with a host of well-known AAA games under his belt — gave a talk about why diversity was good not just for games, but for game sales. “There will be times,” Abernathy said, “when people will use the need for a business case against diversity. But there are at least three good reasons for your game, for your company, for your industry to change with our audience.”

Abernathy’s reasons — moral, creative, and business — create the crux of the argument as to why it’s important for games to embrace diversity and representation in their content much in the way popular culture has. Unfortunately, while moral reasons may be most important to those of us who want to see rich, diverse, complex narratives that accurately represent the intersection of people consuming the medium, the reason that really compels decision makers is, of course, business.

“It’s smart business,” Abernathy declared. “And by that I mean, there is hard data to indicate that everything else being equal, you will attract more players, sell more games, and make more money when you add more gender and ethnic diversity to your game’s cast of characters. […] People like seeing people who look like them in their entertainment.”

The latter supposition isn’t backed up by hard data at the moment, but the demographic shift in gaming is hard to ignore. And since sound business decisions are built on a combination of demographics, trends, psychographics, and the context that ties all of it together, to dismiss the numbers in favor of “conventional wisdom” would mean dismissing a significant chunk of the population that considers themselves a gamer.

“In the absence of a business case,” Abernathy continued, “even teams and companies who are dedicated to diversity in principle can lose their nerve.”

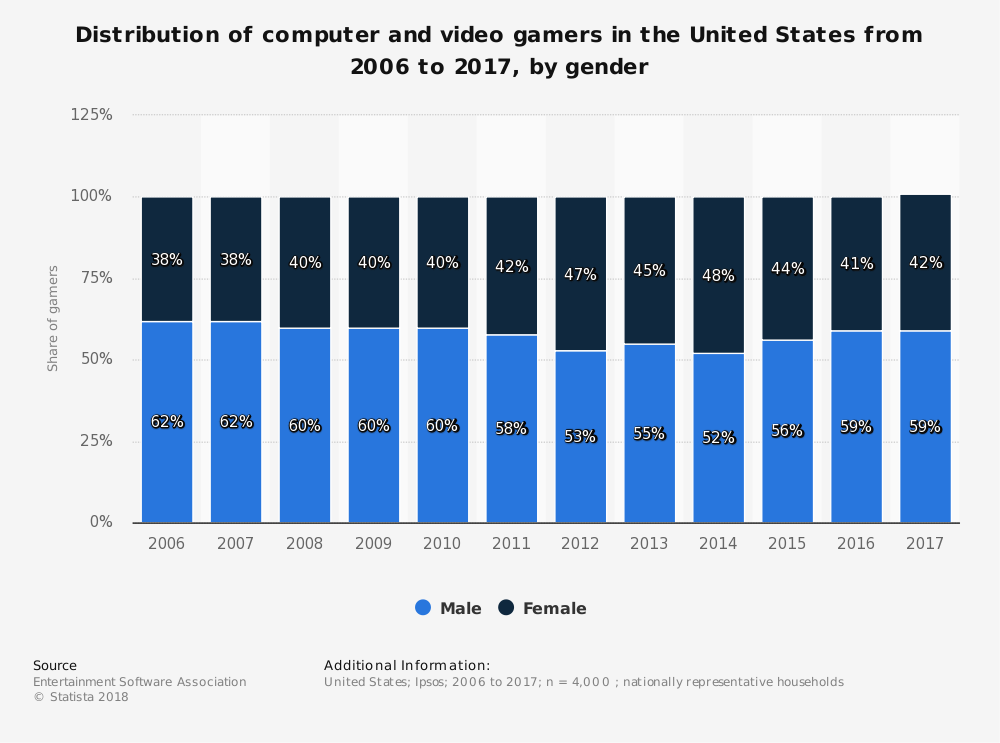

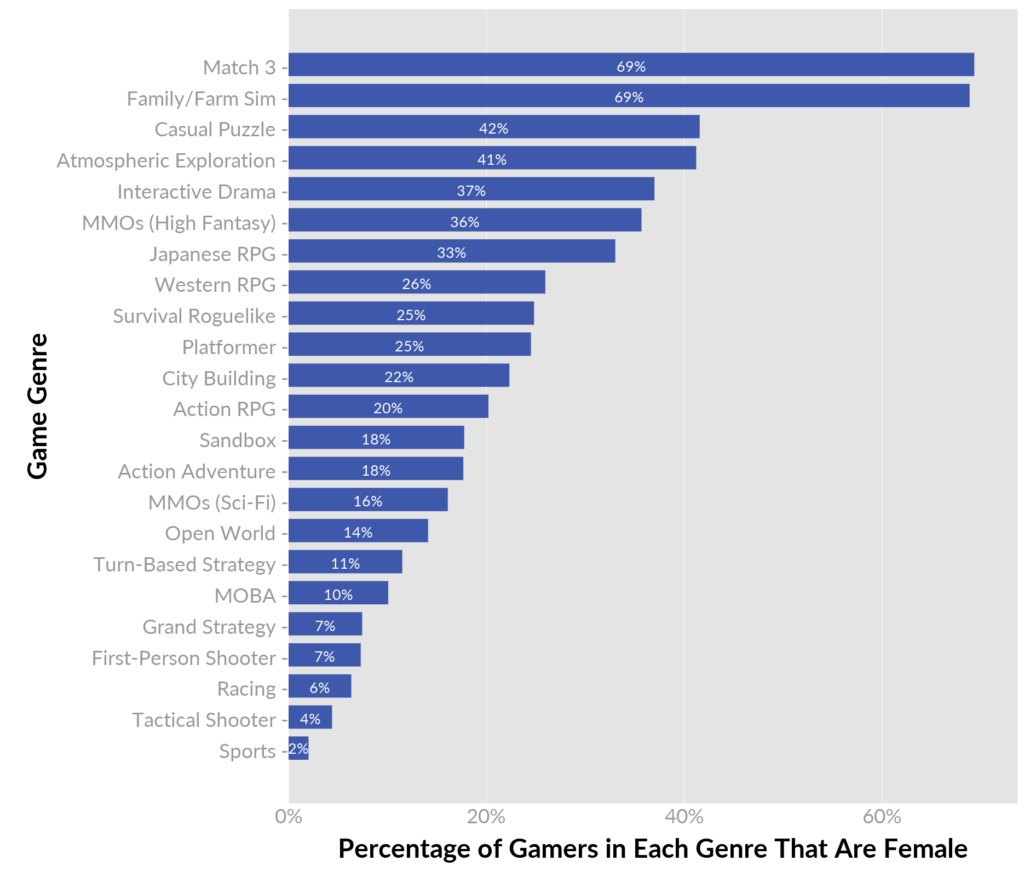

Over the last 10 years, the gender split (not accounting for those gamers who identify as non-binary or genderqueer) among gamers in the United States has slowly shifted towards equilibrium. And while it is true that the majority of gamers are men, the margin has become (for the most part) slimmer over time. Quantic Foundry’s Nick Yee provides a much more nuanced report of the stats provided by the ESA’s annual survey, dispelling a good number of myths that dismiss women as merely “casual” gamers. According to Yee, “Low female gamer participation in certain genres may be a historical artifact of how motivations and presentation have been bundled together and marketed.”

Based on the data, Yee posits that women have steered clear of the more “hardcore” games, like first-person shooters, grand strategy, racing, MOBA, and tactical shooters, because that’s what’s been marketed to the wider audience. Anecdotal evidence may point to an opposing viewpoint, but stories aren’t metrics. They provide important context but can’t be measured against a dataset.

In 2014, Rosalind Wiseman, Charlie Kuhn, and Ashly Burch conducted a survey with 1,400 middle school and high school students across the United States to see what they thought about women in video games. “Our survey was exploratory,” Wiseman wrote on Time. “We didn’t have the resources to conduct a thorough evaluation—but we believed it was an important issue to study and hope others will follow.”

The key takeaways from the survey are: many boys believe that female game characters are seuxalized too often; the protagonist’s gender doesn’t matter to the majority of boys or girls; and girls play a variety of games. According to Statista and the ESA, these younger gamers have the biggest numbers in the United States, which means that their collective buying power will only increase over the next 5 to 10 years in the marketplace.

2013’s reboot of the Tomb Raider series has sold 11 million copies to date, even though sales lagged at the immediate outset. And the 2015 sequel, Rise of the Tomb Raider, has raked in another 7 million sales as of 2017, bringing the series reboot up to 18 million total sales. According to Metacritic, both games were received fairly well by gamers and critics alike. Lara is a known quantity, of course, with her adventures reaching back to the original release on Sega Saturn, PlayStation, and PC (DOS, specifically) in 1996.

As impressive as Tomb Raider’s rebirth has been, Guerilla Games’ (Killzone, RIgs) platform-exclusive Horizon Zero Dawn showed us that you don’t need a known entity to succeed. As of February 2018, about a year after the game launched on PlayStation 4, Horizon Zero Dawn has sold 7.8 million copies. It took multiple years for Tomb Raider to hit those sales figures and Horizon Zero Dawn — a brand-new IP with a strong female lead — achieved that over the course of a single year.

Launching new IP is always a risky investment in and of itself, especially in the AAA console-exclusive space. But Aloy’s charm isn’t the only thing that sold the game — its engaging narrative, enjoyable combat system, and depth of play made for a memorable experience from top to tail. For the most part, Horizon Zero Dawn reviewed exceptionally well among critics and a fair few gamers, too.

On the AA (or Triple-I, if you prefer) side of the industry, there’s Life Is Strange and this year’s prequel, Life Is Strange: Before The Storm. Life Is Strange tugged on our collective heartstrings back in 2014 and, as of 2017, has sold 3 million copies. Square Enix hasn’t released official sales figures for Before The Storm yet, but both games were well-received by audiences and critics.

Sales trends for games that feature women as protagonists see success on the long tail, for the most part. The stratospheric sales that Guerrilla Games’ Horizon Zero Dawn has elicited is a significant data point, both because of the nature of the game and because of its release in the middle of the PlayStation 4’s console lifecycle.

With Shadow Of The Tomb Raider on its way for September 14, it’ll be interesting to see how the game sells in comparison to both Horizon Zero Dawn and its series predecessors. Lara’s final installment in this trilogy may play to the long tail, much like Tomb Raider and Rise Of The Tomb Raider. This will depend partially on whether or not Shadow Of The Tomb Raider will continue to fall prey to the series’ foibles with pacing and gameplay. Additionally, because Shadow Of The Tomb Raider is no longer bound to console exclusivity with Xbox, players on all three major platforms will have access to Lara’s adventures right away. Rise Of The Tomb Raider was locked to Xbox and Windows for almost a year before PlayStation 4 players got access, which may have contributed to Rise’s lagging sales numbers in comparison to Tomb Raider, which wasn’t released as a timed exclusive.

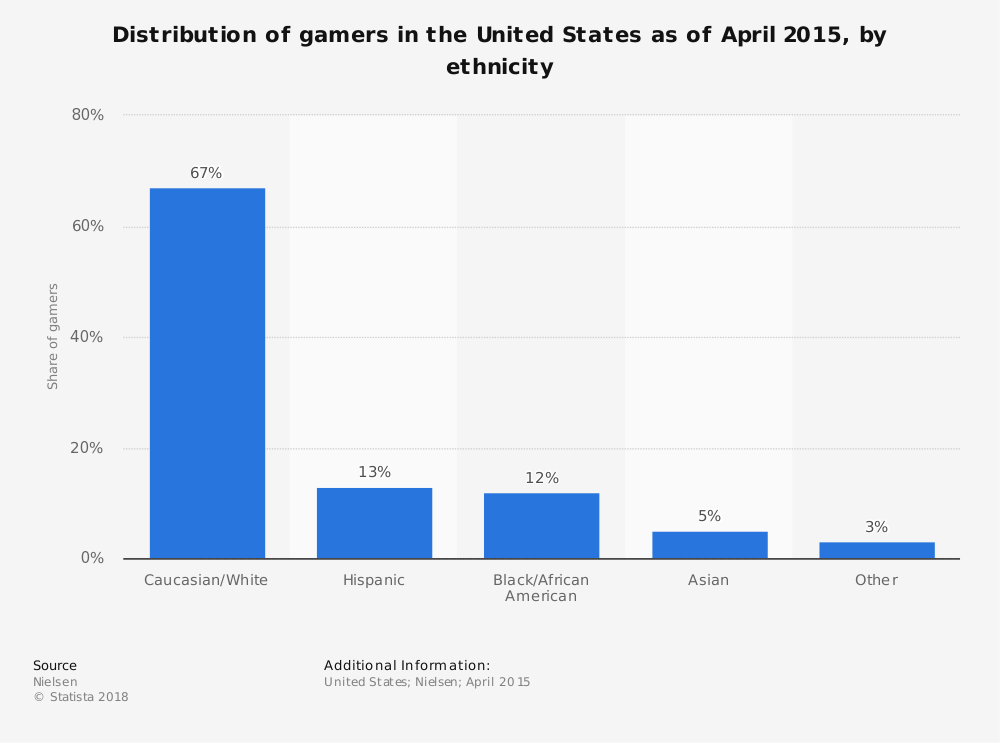

Nielsen reported in 2015 that 67 percent of all gamers identify as Caucasian/White, which explains why the vast majority of protagonists in video games are also white. In that way, the business case for creating white protagonists in video games is, for the most part, strong. However, according to a separate Nielsen study done in 2015, Asian-Americans are 81 percent likely to play games, leading all other races and ethnicities; African-Americans are the next most likely at 71 percent, followed by non-Hispanic whites at 61 percent, and Hispanics at 55 percent.

If we take a sidelong look at the meteoric box office success that “Black Panther” and “Get Out” enjoyed, we can see that previously ignored entertainment demographics can yield extremely positive results for sales.

It’s going to take video games a while to catch up. Long development cycles aside, the game industry can sometimes feel like an ouroboros with AAA studios eating their own tails instead of trying something new. Neither Mafia 3, which sold 5 million copies by Q3 2017, nor Watch Dogs 2 enjoyed the sales numbers that Take-Two and Ubisoft were hoping for. It isn’t to say that the games “flopped,” but neither title did much to move the needle for their publishers.

Assassin’s Creed: Origins, on the other hand, has sold incredibly well, especially after the relatively poor performance of Assassin’s Creed: Syndicate. According to GamesIndustry.biz’s report following Ubisoft’s Q4 2017 financial call, it was noted that Assassin’s Creed: Origins “was the third-best seller in the Europe, Middle-east and Africa region last year.” It’s currently on track to double Assassin’s Creed: Syndicate’s sales.

The Walking Dead: Season 1, the first of Telltale’s seminal adventure series in Robert Kirkman’s universe, starred Lee Everett — a black Georgian teacher — and Clementine — a first-grader whose parents never came home after the start of the zombie apocalypse. The Walking Dead: Season 1 didn’t just tug on heartstrings at the time. It slapped players in the mouth with a brick and left them stunned, but still somehow hungry for what would happen in the next episode in the season. About a year after the first episode debuted, The Walking Dead: Season 1 had sold 40 million dollars worth of episodic gameplay on all major platforms, including mobile. That number, especially before adventure games had found their footing again, was staggering.

And then there’s Overwatch. Blizzard’s competitive first-person-shooter features one of the most diverse cast of characters in the industry. In turn, Overwatch has created a rich fanbase of cosplayers, fan-artists, and fanfiction writers, especially on Tumblr. As of its first anniversary in 2017, Overwatch had made a billion dollars in revenue. Overwatch League has exceeded revenue expectations and according to Dot Esports, the league buy-in for season two could very well triple from $20 million to almost $60 million. Overwatch is very, very big money.

Phil Spencer’s keynote speech at this year’s DICE cemented the importance of player inclusivity in the industry. “This isn’t culture for culture’s sake,” he said, referencing the massive culture shift that has been ongoing at Xbox over the last four years. “It’s culture for collective impact. Cultural transformation is hard, demanding work. We keep at this cultural transformation because we know it enables our best work.”

The industry’s best work is often the result of both cultural change and data-driven business decisions — taking a leap, measuring the trajectory, and scrabbling up the mountain again when met with the inevitability of failure, great or small.

“The easier thing to do is retreat, maybe even deny that there’s a problem,” Spencer continued. “[But] I think that culture can be the tool that enables us to realize the true power and potential in gaming. Studies show that exposure to different cultures and values actually encourages flexibility, and most importantly, creativity. Representation matters, not just for the community they represent but for the world at large.”

From a moral and creative perspective, diversity is a no-brainer. But games are commercial art and they don’t exist just for art’s sake. A goal may be to impact lives along the way, but without a business case that demonstrates that there’s money being left on the table without diversity and inclusivity, skittish decision makers have no reason to embrace any of it, regardless of creativity or morality.

“Giving every one of our players the key to fully unlocking the fantasy that we work so hard to provide them — why are we limiting it?” Abernathy said, closing out his talk. “Our industry, our art, and our businesses stand to gain in every sense simply by holding up a mirror to our audience and reflecting back their own growing diversity as a group. Our products will sell more units because we’ll be making them more relevant and more relatable to more players.”

When it comes to diversity and player inclusivity in games, the industry is playing the long tail, with sales picking up several months after release and remaining steady for a couple of years following. Cultural change comes slowly, after all, and giving the marketplace the opportunity to acclimate is smart business.

These slow-burning trends are indicative of future successes, especially if we look to Horizon Zero Dawn. This isn’t about cultural lip-service or inclusivity for its own sake. It’s about not leaving money on the table by ignoring a large chunk of the consumer base that has access to the discretionary spending that the industry relies on to fund its next ventures. It’s time to hold up that mirror to see the gaps in knowledge and understanding that make for truly exceptional games. Now, more than ever, games have the ability to reach unprecedented numbers of people. In the process, both AAA and indie developers can see their company coffers full and rich, and not just with money.

GameDaily.biz © 2026 | All Rights Reserved.

GameDaily.biz © 2026 | All Rights Reserved.