We’ve heard cries of “indiepocalypse” and “the flood that will crush indie games.” And while discoverability has never been worse, indie games have never been better (or weirder). Fellow Traveller, the publisher formerly known as Surprise Attack Games, has been publishing indie games since 2013. They’ve been behind hit games like Neo Cab, Hacknet, Orwell, and Screencheat — the weird stuff. And what may be a pejorative for other labels is exactly what Fellow Traveller wants to be known for: weird, strange, and beautifully bizarre indie narrative games.

GameDaily chatted with the publisher’s managing director, Chris Wright, about the origin of Fellow Traveller, why they rebranded, how they helped rebuild the Australian indie dev scene, and what it means to be a Fellow Traveller.

In the days of yore, when the Apple App Store was a burgeoning market in Australia, the indie development scene really started to explode. “It was becoming a thing to be indie and it was becoming way more viable for people to go indie,” Wright said. And when THQ Australia went belly-up in 2011, only 18 months after it established itself in Melbourne, Wright didn’t want to throw his cards in with a big triple-A company again.

“I was just like, ‘Oh let’s just screw it, I’ll just set up a publisher myself, like if everyone else can go make a developer why can’t I make a publisher?’” he continued. “Bit of a ridiculous concept really. And it wasn’t like there were lots of indie publishers at that point. There were some but it wasn’t a thing, really. And the original idea was: if bands and other people could set up successful indie record labels in the ’80s and ’90s, then couldn’t games take a similar approach? And that’s something that games needed, because big companies have to work in a certain way — they’re huge.”

But Surprise Attack Games, founded in 2013, wasn’t established as such right away. Instead, Wright started off as a consultant and a “marketing gun for hire.” There were a number of small teams in Melbourne and he had both the experience and the time to start hiring out his experience on a limited basis. He figured that he needed something resembling credibility before he could walk up to indie devs and say that he was an indie publisher that they could (and should) trust with their creative endeavors.

In 2013, the label officially launched at PAX Australia. Wright convinced three developers to sign on with Surprise Attack, even though only one of them shipped.

”The original goal was sign up games from local developers, be very closely connected to them, help the Australian scene recover and publish their games globally.

“The Australian development scene at that time had basically had almost every major studio shut down, and then in the space of another year or so, by like 2014, 2015 they were all pretty much gone. The GFC (global financial crisis) plus the Australian currency doing well made it really tough for Aussie studios.”

Similar sentiments were echoed in Canada, as a number of major studios left the country after the Canadian dollar strengthened during the GFC. Vancouver, BC saw a number of studios, including United Front Games (Sleeping Dogs), Relic (formerly THQ Relic), and Radical Games (Prototype) either gutted or completely dismantled.

It took a few years, but Surprise Attack managed to help the Australian indie dev scene gain some semblance of a foothold in the global market. They’d even worked with League of Geeks on their incredibly successful digital tabletop game, Armello. But Wright knew that if they were going to find real international success, they’d need to focus on the other 96 percent of the world that plays video games.

“The Australian angle was starting to be less of a relevance essentially as we realized consumers don’t really care about where a game is from, unless it’s from where they’re from,” Wright noted. “We were looking at the games we were working on and we basically just made a big list of, ‘What are our favorite games, what are the games that we care about the most?’ [We] put them all on a board and realized that the thing holding them all together was this idea of narrative at its heart — but a lot of the games were just different, fresh experiences. We’d always liked signing stuff that was weird or had great concepts. I grew up playing games in the ’80s and ’90s, when games were just constantly surprising, because people hadn’t figured out what games were supposed to be yet.”

For those of us who grew up gaming in the ’80s and ’90s, weird was the order of the day. Those kinds of weird games, like the mind-numbingly difficult adventure games from Sierra, shaped many a childhood and adolescence. Trends are cyclical and the time has come for weird games to rule once more, it would seem.

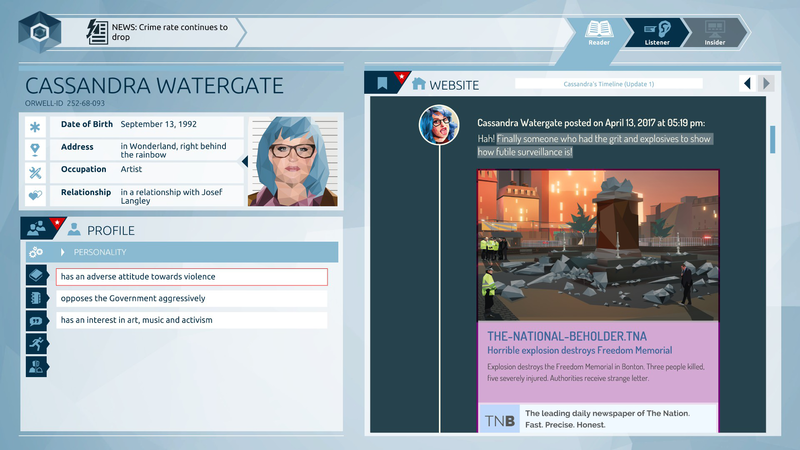

“We’re back at that period where people can just make something that doesn’t play by the rules,” Wright observed. “And small teams are still able to do that. We combined those two things, essentially in that sense of playing something that you haven’t played before, that you feel is a fresh experience, that doesn’t just feel like another one of those kind of games — with story and narrative at its core. So, two years ago we started trying to look for more of those games and sign more of those games. Orwell was the first one and [that] really cemented [the] sense that we were on the right track with this kind of game.”

Fellow Traveller doesn’t want games solely with weird mechanics. They want games with weird narratives and games that tell stories with weird, interesting mechanics. Ultimately, it’s about the story, though. “There is a strong market for games that feel different, that tell stories in different and unusual ways,” he declared. “It’s broader than you think. It’s not necessarily like a real hipster art crowd.

“Orwell was a very strange game and it’s not a surveillance simulator. There’s no mechanic in Orwell really — there’s no way to do well or worse. And yet, we’ve had a very wide range of people come and play that. So for the last two years, we’ve been on that track of knowing this is what we wanna focus on, but needing to sign up more games before we can actually come out and say, ‘Hey, this is what we’re about’, and have that be credible. And it’s taken a while to get through the games that we’ve signed that don’t fit the label either. So, we’ve finally felt at the start of this year that we would have enough games coming up to be able to credibly say, ‘This is what we’re about.’”

When it came time to pursue rebranding, they went through the tried-and-true methodology of finding a new name: throwing word spaghetti at a wall to see what sticks.

And what stuck out was Fellow Traveller. The best part of rebranding with a new name is telling the story behind why you chose it and what it really means.

“We want to be the partner on [the indie developer’s] journey,” Wright explained. “Right from the beginning, that’s the way we’ve described our role — it’s their journey, it’s their destination, it’s their creative process, but we’re there helping them along the way. We’re the Sam to their Frodo, essentially. And our job is to help them get there, and be that.

“But the best thing about it is that we get to go on the journey with them, we get to see behind the scenes, and we get to be part of all those moments that the gamers themselves don’t get to see. They [come in] at the end of the process and there’s stuff that doesn’t get shared. We’re their fellow traveler. [And then] we realized that gamers that love indie games, they’re also like fellow travelers to the developer.”

So after five years of honing what it means to be an indie publisher of “weird narrative games” like Neo Cab and Orwell, Fellow Traveller had a name to communicate who they really were. And since Wright really loves the idea of identifying with the indie music scene of the ’80s and ’90s — the music that fueled his childhood and adolescence — he reflected that Fellow Traveller was going to be like “alternative folk” but for indie games.

“We might be an alternative folk label kind of vibe,” he said with a laugh. “And with the name, that was another big thing we wanted to fit with that kind of sense. So, those [music] labels had that sense of sound. You would listen to something that was on the same label as your favorite band, just because it was on the same label. Because you knew that there was a taste you know, the people behind choosing the bands had a certain taste, and it kind of aligned with your taste.”

With that kind of taste, that kind of sound and flavor, Fellow Traveller has figured out what they wanted to be. But that doesn’t preclude the fact that they’re still kind of the new kid on the scene with their weird narrative games. I asked Wright how he thought Fellow Traveller would be able to differentiate itself from the other indie labels like Devolver Digital, Raw Fury, and Annapurna, in particular.

Wright was a bit wry in response. “No one [has] a flavor really,” he began. “Devolver does, with their sort of punky aesthetic, and obviously Hotline Miami was their big defining moment and they’ve kind of ridden that really well, and expanded upon that, and lived that brand really well.

“But most of the others? I know the guys at Raw Fury really well, and they’re doing a great job, but if you look at their label, they’ve got a great brand, but they don’t really specialize in any particular type of game. [It’s] hard to say, ‘This is a Raw Fury game.’ And there are labels out there like Annapurna coming in. We love to see [this], because we like someone else supporting the kind of games that we like, and they play at a budget level that we don’t play at.

“That’s probably how we differentiate: we’re still very much focused on these small outsider teams, whereas most of the Annapurna titles are from very established, very experienced developers working at a larger budget.”

There’s room for both the triple-I approach to weird narrative games, like Annapurna, and the smaller indie games, like Fellow Traveller will continue to publish. Both matter.

“I think we’re entering a period now where there are so many indie labels and the indie scene has matured so much that indie labels are gonna need to start figuring out what they mean to the consumer as a label,” Wright finished. “[Because they need] to add enough value to the devs that they’re working with, or add more value to the devs that they’re working with.”

Highlighting the indies that need a boost, that need access to capital and to expertise (usually in business and PR), is important. Those are the things that Wright identified as the most requested pieces of the publishing deals that they enter into with indie devs.

Fellow Traveller isn’t interested in a bigger piece of the indie pie. They want to help devs who have been turned away because their game is “too weird” or “too story focused.” And building a label that’s dedicated to producing those “alternative folk” kinds of games means that instead of turning to Steam to curate, Fellow Traveller’s reputation and curated titles will do that instead.

GameDaily.biz © 2025 | All Rights Reserved.

GameDaily.biz © 2025 | All Rights Reserved.