The cultural tides are rising, One More Story Games CEO and founder Jean Leggett and indie developer/Infinity Plus Two communications manager Gabriella Lowgren said in a talk attended by GameDaily at Game Connect Asia Pacific (GCAP) about dealing with mature and traumatic content in games.

We now have biographical games, like Depression Quest and That Dragon, Cancer, that tell personal stories, and efforts like Spec Ops: The Line — which explores the horrors of war — along with the burgeoning field of serious games, all of which challenge the traditional view of games as entertainment. And with the tools of game development becoming ever-more accessible, we’re seeing more diverse teams make greater numbers of games that in turn reflect more diverse and at times more serious themes such as sexual assault, gender dysphoria, post-traumatic stress disorder, or any number of other sensitive subjects.

“An experience doesn’t have to necessarily be a really beautiful, lovely experience to get something across,” said Lowgren. “There is value in creating art and creating experiences that can be harrowing and can be raw and can be real.”

Both women emphasized that game developers have a responsibility and an ethical obligation to do right by their audience in terms of how they treat sensitive subjects, but they added that many people in the games industry don’t currently take these obligations seriously.

“You make these games and you tell your story, and then what we forget is that they resonate with people,” said Leggett.

That means it’s important to be upfront with trigger warnings so that players can know what they’re getting themselves into, because some of the content could be potentially traumatic to experience, especially for people with a personal connection to the themes, and it means that the key feeling to evoke is not shock or anger or confusion. It’s empathy.

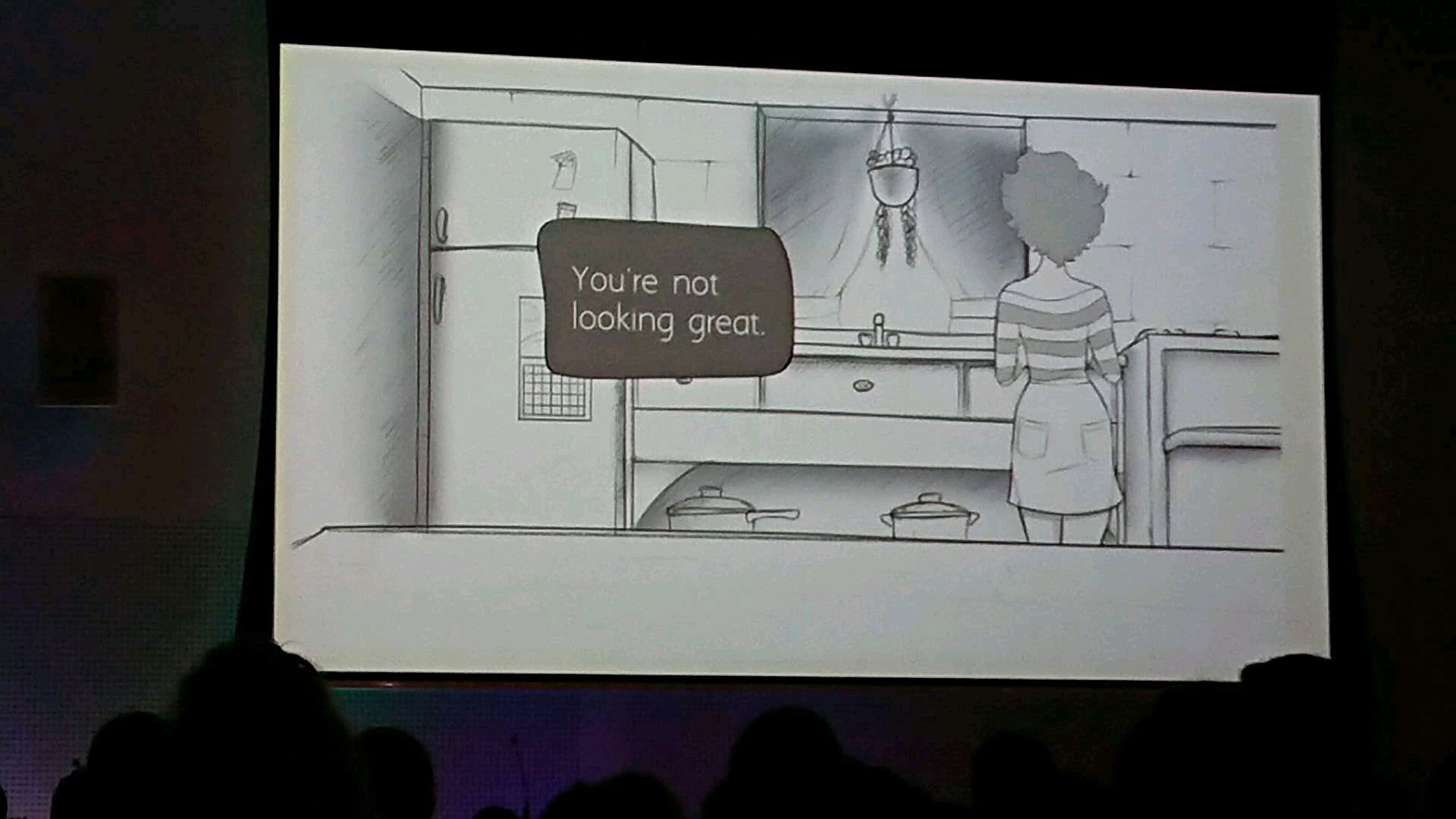

Lowgren, in particular, wants players to empathize with her game characters. To help do this, she said, it helps to have gender-neutral characters so that players can more easily project themselves into the experience. In her game Shrinking Pains, for instance, the player controls a nameless character of unspecified gender and appearance — referred to only as “you” — who has anorexia.

“Using second person makes it so immediate, and it does make it a little bit uncomfortable,” Lowgren explains. “It’s a way to get you to really connect with the lived experience. Also what I think is really important in Shrinking Pains is the illusion of agency. I believe that immersion plus agency equals increased chance of fostering empathy.”

Only having an illusion of agency is critical here because when it comes to mental illness, there often is no choice. In Shrinking Pains, the game presents some choices as blurred and grayed-out — because sometimes, even if there is food available, eating is not an option for a person with an eating disorder (as they are repulsed by even the thought of food).

“Of course [playing a game for] half an hour is very different to living with an illness, but it gives you even that little bit of insight and that little bit of empathy, which can make a huge difference in our world,” Lowgren said. “The more that we talk about these issues, and have empathy for these issues, the more we de-stigmatise these issues, and we can further the conversation away from just being diagnosed to being treated to being accepted and loved and supported — by society and by your interpersonal relationships as well.”

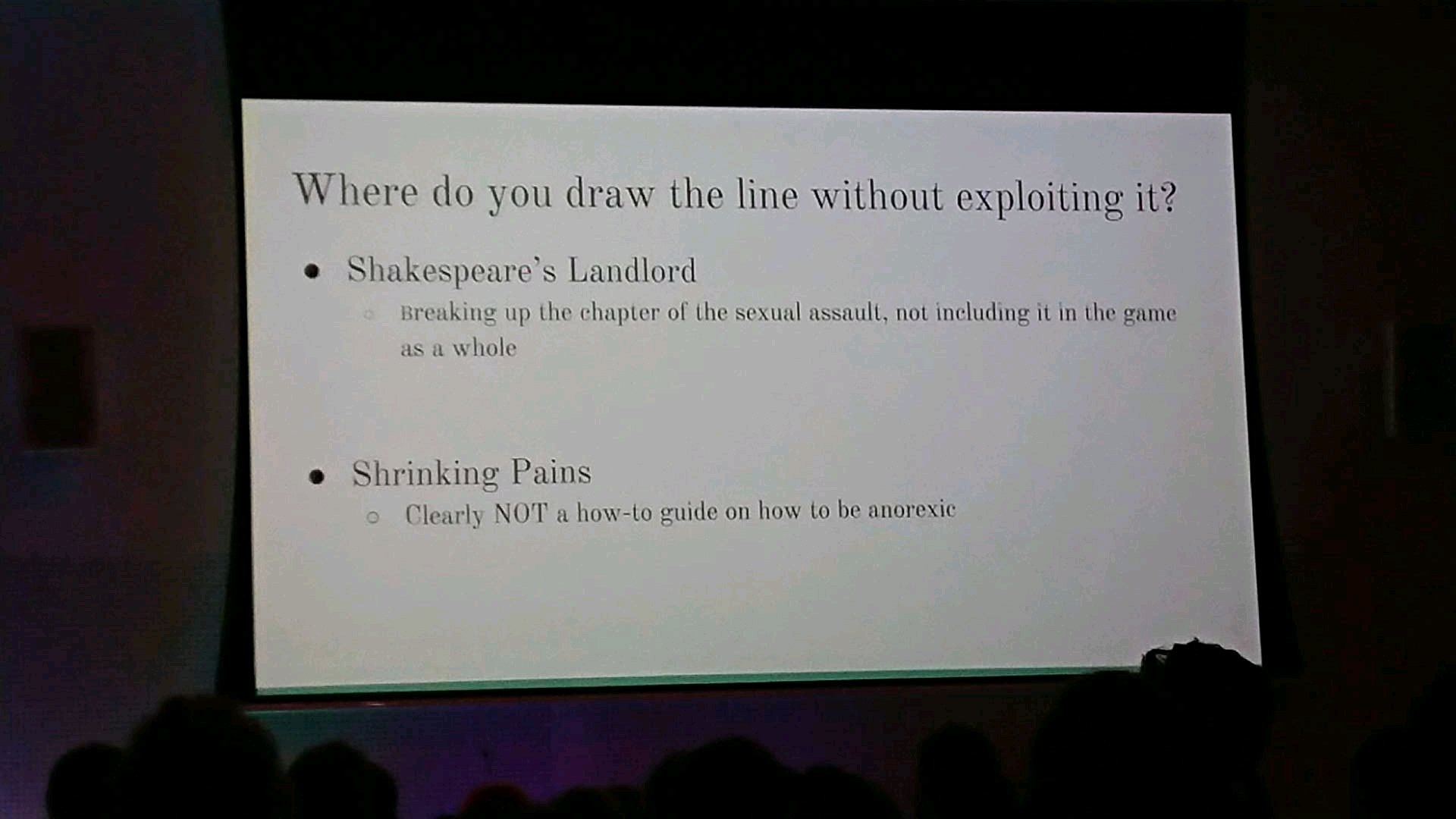

Games that explore themes like sexual assault and eating disorders tread a fine line between empathy and exploitation, however. Not every experience should be gamified. In Shrinking Pains, for instance, Lowgren knew she needed to avoid making a how-to guide on anorexia.

“I don’t want to give people ideas on how to hide their disordered eating or how to participate in disordered eating,” she explained. “Because I think that is one of the worst things we could have possibly done within Shrinking Pains itself.” Players see the character’s reaction to food and the idea of eating, but never any of the actual habits of that disordered eating.

Finding that line is not always such an easy thing, Leggett noted. Her studio has been working on a game adaptation of the Charlaine Harris novel Shakespeare’s Landlord for a year and a half, and they’re still trying to get the feel of the experience right.

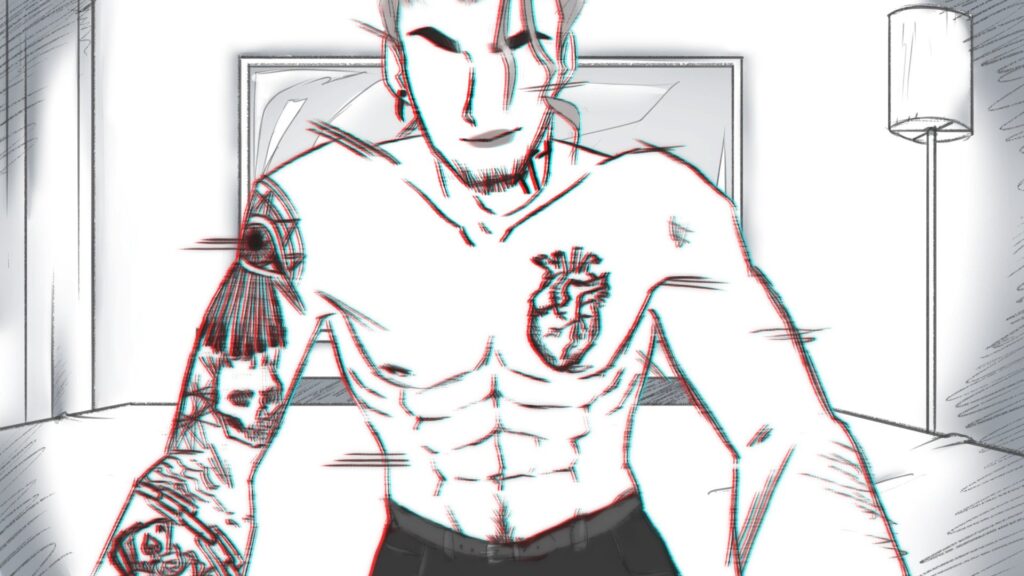

Leggett showed how an earlier version of the game used a black and red “horror”-styled color scheme for flashback and nightmare images when main character Lily — who was abducted, sexually assaulted, and mutilated by multiple men prior to the events of the game — finds herself stressed or anxious. That aesthetic didn’t sit well with Leggett after she reflected on “inconsistent art style” feedback from IndieCade judges last year, so the team shifted to monochromatic imagery with faceless shadows to better reflect the experience of survivor PTSD.

They knew they’d got it right with this monochromatic style, she added, when she showed the new art to a couple of survivors who replied that “it’s always the faceless men in my nightmares.”

Even then there was still a careful balance to seek. At one point one of the artists had drawn an image to represent a rape nightmare, with a man holding a woman down. They cut it from the game partly because of concerns it may be too graphic, but also because they reasoned that the narrative should be able to convey the underlying ideas and meaning with better nuance than a single image ever could. And indeed, Leggett added, by making these careful considerations the game as it stands now is much more nuanced than they originally set out to make it — which is in keeping with the complexity of real survivor experiences.

Similarly, Lowgren’s Shrinking Pains tells its story through a series of snapshots which contain ever-decreasing environmental detail — to the occasional wonder of the main character, who questions if their world always looked so non-descript. Together these function as a metaphor for how anorexia sufferers “lose” time and vision as their brain struggles to function without energy.

Design metaphors and nuanced writing like this can be powerful vehicles for developing empathy and understanding when it comes to characters afflicted by mental illness or traumatic experiences. Leggett recalled a moment early in development when her husband, who is one of the writers on the game, came to her concerned about how they would handle the contents of chapter 5 — which is the one where Lily recounts to another character all the gory details of her abduction.

They decided to avoid gamifying that experience and instead try to spread the memories in a nuanced way across the whole game — through the flashback images and sound effects, snippets of dialogue, and entries in a diary that they created for Lily (she didn’t have one in the original novel). And they also discussed parts of the story with professional advisors, who offered invaluable feedback on how to portray sensitive issues in the game with kindness and knowledge.

Leggett revealed real-world statistics that a person is sexually assaulted in America every 98 seconds — a number that she thinks underscores this need for game developers to treat sensitive issues ethically and responsibly. And she added that developers should not shy away from it just because it is hard. Sexual assault and mental illness, especially, remain stigmatized in our society despite their high prevalence — even affecting men in the armed forces, Leggett learned from speaking with a psychiatric nurse after a recent talk in Houston.

“We need to tell these stories, most importantly, so that people don’t feel like they’re alone,” Leggett said. “And also understand that these are survivable things. I’m willing to bet that most of us have had some trauma in our lives, and hopefully we’ve had the opportunity to find the process to get us through that trauma and to heal from it.”

And games, with their sense of agency and immediacy, provide a great outlet through which that can happen — even if, Leggett admitted to me during a brief chat at PAX Aus a few days later, there’s a small segment of the gaming audience that will likely harass and threaten her (and anyone else making an effort to tackle serious subjects in games) for challenging the old idea that games should be escapist fantasies. Because, she re-emphasized, games that deal with sensitive issues tend to resonate with people, and because, in the wake of social movements like MeToo, the world is now ready for stories like this.

For Lowgren, whose Shrinking Pains was based in part on personal experiences of living with an eating disorder, this point rang particularly true. Shrinking Pains has been widely played and streamed, she said, and many reviewers on Steam have commented either that it gave them new insight into anorexia or helped them to understand what a loved one with the disease is going through. Meanwhile, many people with eating disorders also reached out privately to thank her and her collaborators for making the game.

“A big part of an eating disorder or any mental illness is feeling isolated and alone because you are not functioning the way you are taught you should function, or the way that society models a stand-up member of a group,” Lowgren said. “And they felt seen and acknowledged in that moment, even though it was hard to play. It made them feel human and connected to something. And that was really powerful. And I didn’t expect it.”

“I could never have imagined that something so beautiful could come out of the ugliest part of me,” she added.

GameDaily.biz © 2025 | All Rights Reserved.

GameDaily.biz © 2025 | All Rights Reserved.