Martin Stig Andersen, the Danish composer perhaps best known for his work on Limbo and Inside, grips a distressed-looking human skull in his hands. Notable is the absence of a jawbone. He wheels his chair across the room, gently puts down the skull, and comes back with another boomerang-shaped piece of bone.

That is the accompanying jawbone, mounted with a metal rod on a pearly white stand. The jawbone, too, is missing something.

“There [are] no teeth left. They all fell out due to the vibrations,” he said while rotating it around.

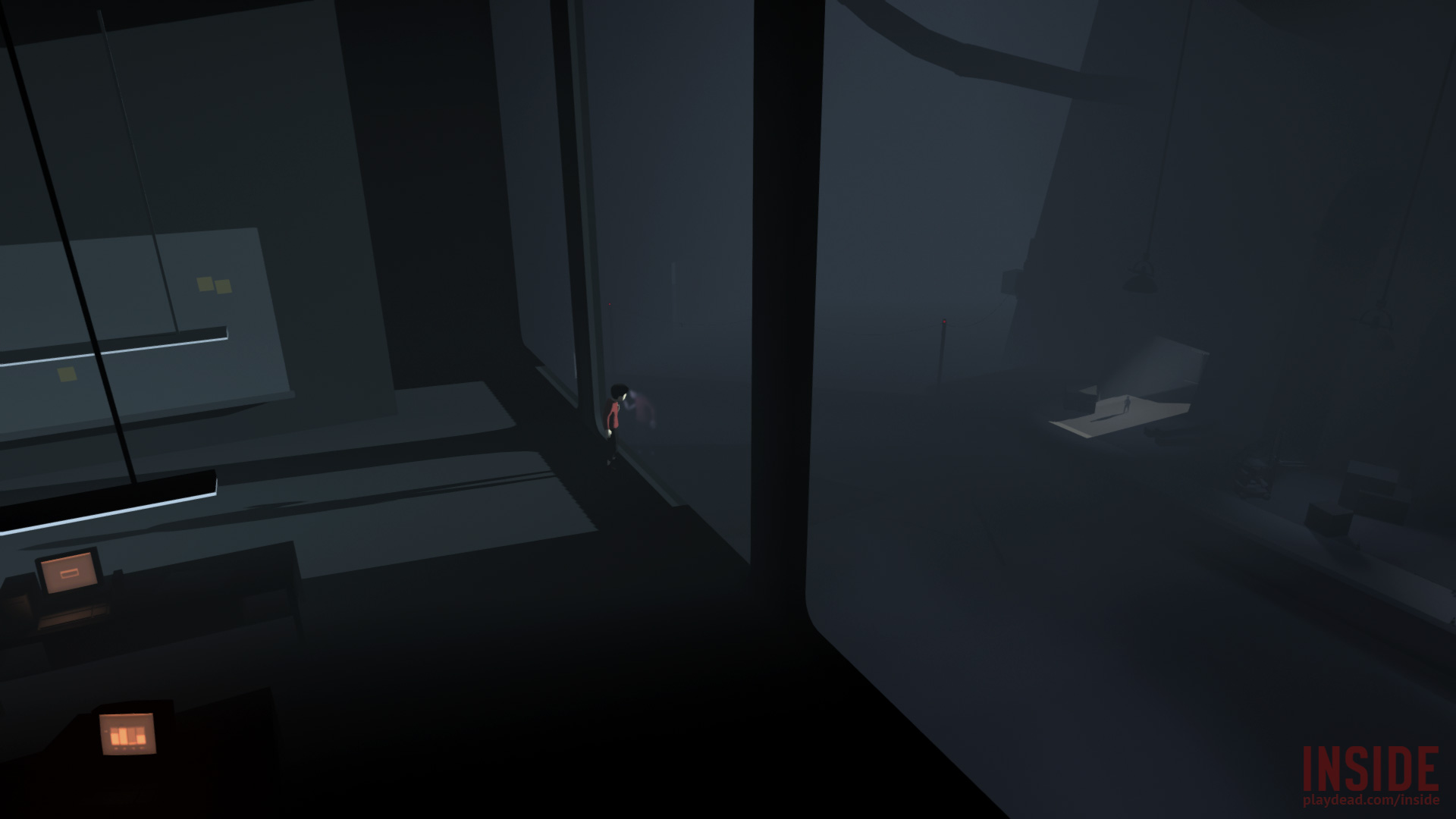

Andersen used the skull to color the eerie sounds of Inside and give the game a unique ambience.

If you have ever recorded yourself speaking and then listened to the sound played back, chances are you will notice a shocking disparity between how your voice sounds in your head versus what you are hearing come out of your speakers or headphones. This is because a large amount of the sound we hear when we talk is being conducted through the bones in our skull.

Andersen’s idea to filter the sounds of Inside through a skull came from a Stanford University research paper which described attempts to simulate the effect of how one perceives their own voice in their head on a recording using post-processing techniques.

During Inside‘s pre-production phase, Andersen says he had a lot of time to experiment with different sounds and that was when his idea for using the skull as a medium for his compositions became reality.

“At the time we didn’t know the game was going to be called Inside,” he noted with a chuckle of irony.

He compared the skull to a speaker without a membrane. Using contact microphones attached to the jawbone and a sequencer with a plugin that Andersen aptly titled “skully,” he deconstructed different sounds played through the skull and then digitally repaired them in post-processing.

Composers are always looking for not just unique sounds, but relevant ones. It’s one thing to go off the beaten path, but quite another to do so in a way that is purposeful to the project they are working on.

Mick Gordon told us as much when discussing his creative process recently. For instance, Spinal’s theme from the 2013 release of Killer Instinct is composed of a Tibetan kangling, a full brass section, electric guitars, and a chorus of men singing in Swedish. It was an ambitious piece, and the recording process spanned five countries over three months.

None of the song’s disparate elements are haphazardly thrown in, though. They each have a purpose. Take the choir, for instance. Gordon was given concept art and backstory for Spinal which informed his choices. For Spinal, what he knew was that the character was a viking-themed warlord who was murdered on the open sea, and that he eventually became a godlike figure to his people. Future warriors would chant to their warrior God in an attempt to resurrect him to aid them in battle.

Gordon thought, “Wow, what would that chant sound like? So you try to give that chant an identity, and you build the track around those ideas.”

“I work in a really unique and interesting industry. I’m in a unique position where a lot of the inspiration is handed to me. Not the ideas or the music itself, but the inspiration,” he said. “And so when you’re working with that, there’s always inspiration. There’s no chance of a brick wall.”

Austin Wintory, the composer behind the music of Flow, Journey, and mostly recently The Banner Saga 3, also does not struggle with generating ideas, but he does face other pitfalls.

“I can say honestly, and I don’t mean this to lack humility, that a shortage of ideas has never been the issue. If anything, the opposite has been my struggle: a paralyzingly overwhelming number of seemingly-viable options. I have many times struggled to move forward with a piece because I can simultaneously imagine so many ways of approaching it.”

Taking a bow at the Colorado Symphony following the premiere of A Light in the Void, Wintory says, was his proudest accomplishment. He and writer Anthony Lund Kickstarted the project, describing it as a blend of live symphony, theatrical performance, and TED Talk.

“That project very nearly killed me and was by far the most ambitious thing I’d ever attempted,” Wintory exclaimed. Feeling it successfully executed was almost indescribable, but mostly a huge relief!”

In spite of the nearly half-dozen awards he has earned, the widespread acclaim of his music, and the success of the projects he has worked on, Wintory wrestles with an ever-present demon: Imposter syndrome. Imposter syndrome is characterized by feeling like you are incompetent in spite of evidence to the contrary. It makes one feel like a fraud simply biding their time until they are exposed as unskilled or incapable.

“Every day comes with an idle dread of being ‘found out’ and all I can ever manage to do about it just forge on ahead as best I can.” Wintory said. “Self-care is an ongoing negotiation. I, for many years, did nothing on this subject. Purely just kept my head down to keep working. Pushing longer and harder all the time. Only lately have I been giving myself more free time.”

For The Order, Ready At Dawn flew Jason Graves out to Irvine, California early in the pre-production phase of development. For three days they talked about environments, narrative themes, and perused concept art.

After nine months Graves could finally send them a few minutes of music as a concept test. Over the next six months he and Ready At Dawn hammered out the details for what type of instrumentation Graves would be using in his score. Another six months passed while Graves wrote the rest of the game’s music. Finally, a year after that they were finally ready to record the live music that would eventually bring The Order’s soundscape to life.

While all of this was going on, Graves was working with a very different process for Evolve. He likened his work flow on Evolve to when he would compose music for Ubisoft titles like Blazing Angels where he would get a few pieces of concept art and an Excel document. In said document, he would find dozens upon dozens of cells with labels like “Exploration 1-10,” and “Combat 1-10,” with notes saying how many minutes, or even seconds, long each track needed to be. Occasionally he would also receive notes indicating, for instance, one of the exploration tracks was for a section set in the Adriatic Sea.

He worked intensely over the two months that his work on The Order and Evolve overlapped. Graves found himself having to be extremely particular about his physical well-being and self-care during that time.

“So I was literally doing 4-5 minutes of music a day, completely finished from beginning to end, for two different games and also pretending like I was training for the Olympics: In bed by 10 o’clock at night; Three meals a day and drinking plenty of water; No alcohol.”

He added that, “Mentally, the only time I get to the point where I’m like “This sounds awful. I have no idea what I’m doing. I can’t even hear what I need to do next,” is because I’m physically tired.”

Recently, on the fifth day of working on a cue for a television show, he found himself exhausted and fearing the worst.

“I sat there and thought, “That’s it. They’re gonna fire me. I’m done. I’m just gonna have to call them and say I can’t finish this cue.” And that all flashes through my head in a tenth of a second, and then I just take a breath and say to myself, “Just get it done.” And then I start composing more, putting more notes in, massaging it until it sounds like it’s not completely horrible.”

For all of his doubts and self-criticism, the irony is that the music he submitted was approved immediately with no corrections needed.

“For me, if I’m tired, I’m my own worst enemy,” Graves admitted.

“I think the doubts are like a necessary evil. You don’t want to get rid of the doubts.” Andersen said. “But at the same time you have to take care that those doubts don’t rip you apart.”

For Graves, the solution to a healthy relationship with his inner critic is through taking care of his physical well-being. For Andersen, meditating, exercise, and vacations give him a reprieve from when his doubts become particularly vicious.

And Gordon uses his doubts to keep himself vigilant. He deals with imposter syndrome, but he, too feels like it is a necessary evil in moderation.

“Everybody should be feeling that imposter syndrome to some regard. The moment you step in and go, “I am meant to be here. I know exactly what I am doing 100% of the time,” That’s when you should be worried,” Gordon said.

“For all kind of aspects in my life, only a few rewards came without pain. That’s the same in composition. You have to go through some pain to get somewhere interesting,” Andersen added.

Artists have always had to find ways to transcend the omniscient combination of imposter syndrome, obsessive tinkering, and the loud voice of their inner critics. A common theme in talking to Martin Stig Andersen, Mick Gordon, Austin Wintory, and Jason Graves, is that they are all racked with doubts. They criticize themselves with what sometimes appears to be harsh scrutiny, but they all have learned to take advantage of their inner critics without being consumed by them.

GameDaily.biz © 2025 | All Rights Reserved.

GameDaily.biz © 2025 | All Rights Reserved.