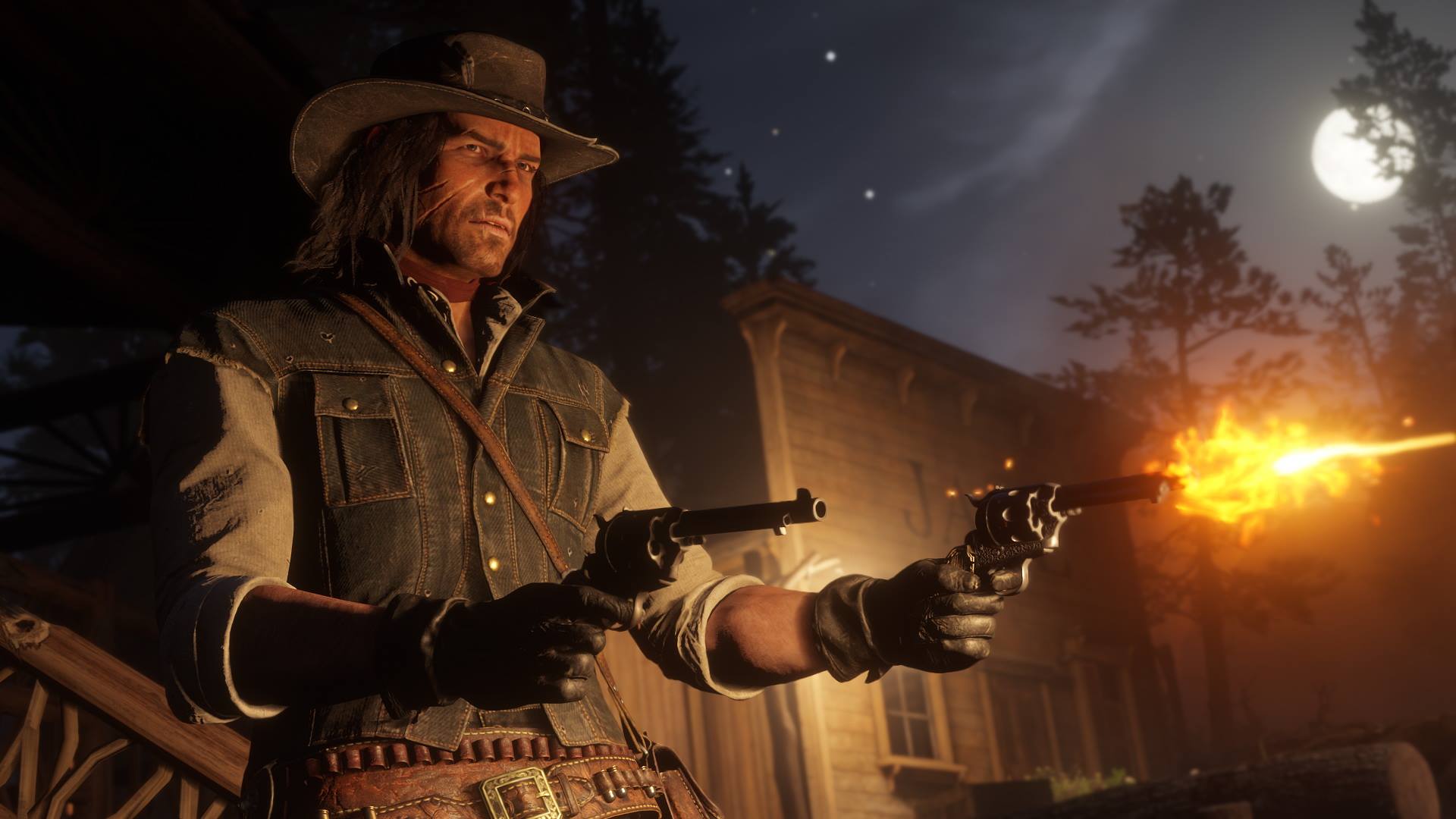

Red Dead Redemption 2 is one of the most anticipated games of the year. In less than two weeks, it’ll be in the hands of (likely) millions of consumers across the globe, many of whom are probably oblivious to the arduous task its creators wrestled with for the better part of eight years. In a new interview with Vulture, Rockstar’s co-founder Dan Houser revealed that he and his team worked intense 100-hour weeks recently in the run-up to launch to polish a game that’s absolutely massive, containing 60 hours of content with 300,000 animations and 500,000 lines of dialogue.

The games industry is no stranger to crunch, an issue that some believe is getting better, but clearly the latest revelation from Rockstar shows that the games business still has a ways to go. Rockstar itself was accused of pushing its San Diego employees to regularly work 60-hour weeks for the original Red Dead Redemption. To be clear, Houser quickly followed up on the interview by issuing a new statement to Kotaku, stressing that no one was forced to work extra long hours and that the crunching only occurred with a small, core team.

“After working on the game for seven years, the senior writing team, which consists of four people, Mike Unsworth, Rupert Humphries, Lazlow and myself, had, as we always do, three weeks of intense work when we wrapped everything up,” he said. “Three weeks, not years. We have all worked together for at least 12 years now, and feel we need this to get everything finished. After so many years of getting things organized and ready on this project, we needed this to check and finalize everything.

“More importantly, we obviously don’t expect anyone else to work this way. Across the whole company, we have some senior people who work very hard purely because they’re passionate about a project, or their particular work, and we believe that passion shows in the games we release. But that additional effort is a choice, and we don’t ask or expect anyone to work anything like this. Lots of other senior people work in an entirely different way and are just as productive – I’m just not one of them! No one, senior or junior, is ever forced to work hard. I believe we go to great lengths to run a business that cares about its people, and to make the company a great place for them to work.”

While Houser’s clarification definitely paints the picture in a different light, it still does not diminish the fact that management does seem okay with the idea of crunch in general, even if it’s not insisting that everyone participate. And this kind of normalization is problematic for an industry that’s struggled to get past the issue since the days of “EA Spouse.”

Jen MacLean, executive director of the International Game Developer Association (IGDA), commented to GameDaily, “When we normalize, or–even worse–brag about, 100-hour workweeks, we harm our fellow game developers. Sustained overtime has been proven time and again to have severe detrimental impacts on a person’s mental, physical, emotional, and financial health. No game, no matter how many units it sells or how many awards it wins, is worth the human cost of damaging the lives of its developers.”

The problem with management engaging in long hours, even if they tell others down the food chain not to, is that it leads to implicit pressure among the teams. Alex Bethke, best known for the self-published indie game Fate Tectonics has worked in the industry for 15 years on more than 100 projects and has seen what happens to developers who crunch at medium to large studios.

“There’s always a problem when there’s disparity in effort on a team. Those that are working harder eventually feel resentful to those working less. Those working less feel pressured to match the efforts of those working unsustainable hours. Both sets of groups can be played off of each other for the benefit of the stakeholders in the project who get the actual profits at the expense of the team’s health and well being,” Bethke noted.

“Veterans in the industry, the few that survive the crunch for any length of time, and this is something I myself have been guilty of over the years, begin to wear their ability to crunch like a badge of honour, further reinforcing the bad culture and directly and/or indirectly saying to newcomers, if you want to have even a chance of getting to where I am you need to sacrifice everything.”

The world has waited almost eight years for a sequel to Red Dead Redemption. After all this time, it’s unfortunate that 100-hour weeks were still deemed necessary. Rockstar and parent company Take-Two already delayed the game once before. Isn’t a little extra time worth it so no one has to endure crunch?

“The truth of the matter is there is nothing inherently life or death about the games industry, despite it being a multi-billion dollar industry, and as such all deadlines and the related pressure to hit those deadlines are completely fabricated,” Bethke remarked. “Not shipping a game has never impacted someone’s health that I am aware of, but trying to ship games has ended families, marriages, and in some extreme cases led to significant health problems.”

Bethke isn’t kidding. When he lost his own father, he went to work the very next day because of crunch: “When I was running my studio my dad died suddenly and I felt so pressured by an upcoming deadline with what turned out to be one of our worst clients ever, I came to work the day after. This was despite my business partner, our business mentor, and the studio’s lead artist all trying to get me to stay home. In hindsight it’s become very clear to me that the project didn’t need the crunch since the deadline could/should have been moved, the client certainly didn’t deserve that kind of loyalty, and I more than likely hurt myself by not grieving properly, despite usually finding solace during emotional times by throwing myself into my work. Crunch gets in your head and messes you up your priorities is ultimately my point.”

When you’re an indie or running a small studio, sometimes you feel like you have no choice. It isn’t a case of answering to the “big, bad corporation.”

Amanda Gardner, who founded The Deep End Games with her husband Bill (the former design director on BioShock Infinite), commented to GameDaily, “I’m more about being cognizant of your limits and taking care of yourself if you’re going into a long-haul type situation. Crunch for us on Perception was a long time partially because we’re a tiny team working from home, and there seemed to be times where there was no end in sight because we just kept pushing ourselves. This was all up to us, indie spirit, all our eggs were in this basket. We HAD to.

“I remember propping Bill’s head up with a pillow while we finished Perception and his parents coming at all hours to give him a coffee and a hug. We were both so sick with mono that we could barely function. And then there were the babies, one just months old and the other just over a year. We had to take care of them, too, but we were so run down it was hard. But we pushed ourselves too much, it wasn’t someone looming over us. We chose this, and we didn’t manage our bodies well enough. It takes a personal toll. I know that in future projects, when other people would have to crunch with us, that we’d be very careful about how that all went down.”

If you’re in a position to manage other developers and you’re asking them to crunch, it’s probably a sign of bad management, Bethke points out.

“In my experience I’ve found that crunch, at the corporate level, is always due to a failing on the part of management,” he said. “That failing could be due to bad planning, not valuing their employees’ efforts, health, work/life balance, or other factors, but it ultimately comes back to management making the decision to extract free work from their staff rather than spend more money on the project. Obviously there are many factors that come into play, the simplest being that there might not be enough money remaining in the budget to allow them to extend the schedule, but, budget shortfalls are the responsibility of the management team, so again, I put the blame on them.”

Budget is certainly not a problem for Rockstar, but Dan Houser probably should not be talking about the 100-hour workweeks as a badge of honor either. It’s just sending the wrong message — and not just to developers, but to the consumers, Bethke believes.

“A company should NEVER be advertising the fact that they crunch in anything but an apologetic manner and definitely not as a point of pride. Corporate imposed crunch devalues the efforts of the team, which devalues the efforts to the consumers – by extension this has been a contributing factor to the consumer ideology that games should be free and the subsequent rush-to-the-bottom pricing we see across the industry but especially on the PC and mobile markets,” he explained.

“Crunch as part of the culture of game making, something I have definitely been a victim of over the years, leads to valuing work over all other aspects of life – health, relationships, family, friends – and has detrimental and long lasting effects. The people that crunch are seldom properly compensated for their efforts while management reaps the rewards and any time the crunch yields a positive result it reinforces the value of crunching to management, continuing the cycle. Related to this is the idea that only the most passionate people succeed in this industry and if you aren’t willing to crunch then you lack passion and this is often used against staff time and again. First at the hiring level, then later on when trying to negotiate better compensation and/or work/life balance.”

Red Dead Redemption 2 isn’t an isolated case. It’s just the game making headlines now, but crunch sadly permeates the industry at studios big and small, and it’s going to take a change in culture ultimately to set things right. As Jennifer Scheurle, Game Design Lead at Opaque Space, tweeted today, “Gamedevs live in a weird culture where not working like a horse and not playing games every day after work makes people question your dedication to a job that we are made to believe everybody should be dreaming of. Don’t underestimate how insidious that is.”

GameDaily.biz © 2025 | All Rights Reserved.

GameDaily.biz © 2025 | All Rights Reserved.