Game development is an artform, but developers don’t often think about what they can do to ensure they’ll be able to keep the lights on long enough to craft more beautiful games in the future. If a studio is not sustainable, all the creativity in the world won’t help. That’s why Zoe Bell, Lead Producer at Baltimore-based Big Huge Games, is giving a talk on “30 Concrete Changes You Can Make to Make Your Team More Sustainable” at the IGDA Leadership Summit on September 14th in Austin, Texas.

As a media partner for the event, GameDaily had a chance to catch up with Bell to get a preview in advance. We’re not going to steal her thunder and spell out the 30 changes, but at a high level, Bell explained that all of the items on her list fall into main categories, such as product choices, long-term thinking, and trust.

“Sustainable teams make strategic product choices,” she said. “What type of game are we going to make? They are always thinking long-term about the growth of the team and the visibility of the team, and then there’s two-way trust. A lot of [the keys] have to do with making sure that management trusts the team to do what they do best, and the team trusts management because management is communicating, and sharing, and being open, and all of that kind of stuff.

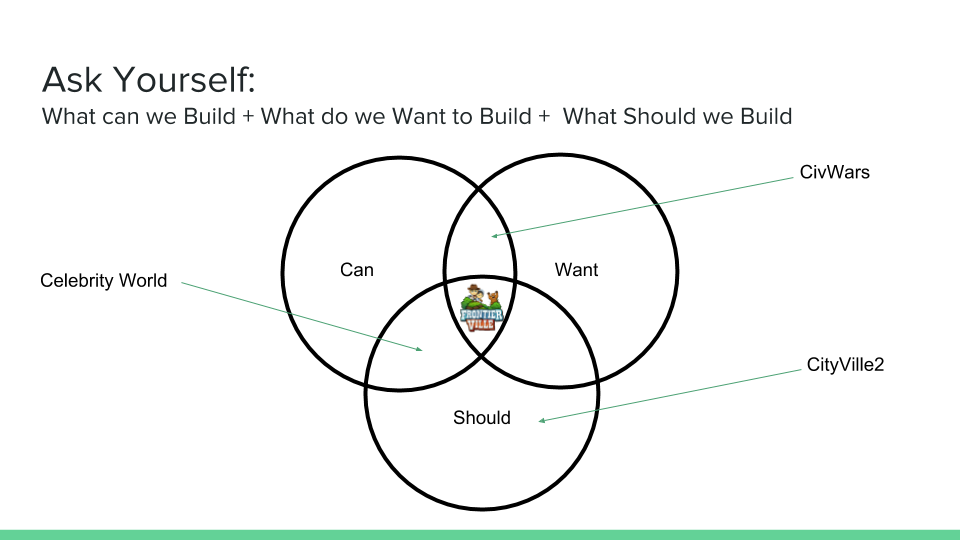

“One of the things that we always ask ourselves when we’re thinking about what product we’re going to make is, ‘What do we want to build, what can we build, and what should we build?’ Those are the key things. I think that sometimes people say, ‘Well, what do we want to build and what can we build?’ And they forget about the market. Any time we’re making a product, we’re just always, always, asking and trying to find the center of that Venn diagram.”

For indies, in particular, keeping in mind the market and prospective audience for the game they are looking to build is not an easy task, especially if they’ve had zero business experience in the past.

“You’re an indie developer — you want to make a super, awesome game but you want to make another game at some point, and another game after that,” noted Bell. “I saw a talk at MIGS [Montreal International Game Summit] last year by the Cuphead developers, [StudioMDHR]. They were talking about how …they did mortgage their house and whatever, but they didn’t do that right away. It wasn’t their first step to take out a second mortgage on their house; their first step was to get little test pieces of feedback and make sure that people like this crazy game they were making, and I think a lot of teams don’t do that.

“And when you’re at a bigger company, what does that translate to? That’s doing usability throughout your development process to make sure that people are understanding what your game is about and enjoying your game, and that is how you avoid getting in that situation where you made this game and you’ve invested two years of time and now [you feel forced to launch it anyway].”

Game design is an iterative artform and a chunk of the time, projects just don’t work out. Understanding when to cut your losses and move on is crucial. The so-called “fail fast” approach is certainly a key to sustainability and Bell advises that developers learn to factor that in.

“I think, thinking that you’d be lucky if 10 percent of your games were a hit, is the key part of it, and that’s one of the things that I want to cover,” she said. “When you’re thinking about how much money you need to make a game, you can’t just [do that in isolation]. If you just want to make one game and then you’re out of business or you’re a huge success, that’s okay. But if you’re trying to build a sustainable team, you need to think about, ‘How many games is it going take for us to make a hit?’

“Your strategy could be to keep trying different shots in the dark or to try one and see if you can get medium success, and then build upon that. I think all those are valuable theories, but you have to have a strategy there.”

Bell has worked with companies large and small, including Zynga East, Zynga’s headquarters in San Francisco, DeNA, and Kongregate. Big Huge Games has the small company feel still, but it’s benefitting from the corporate backing of Nexon. Bell has seen the pressures of sustainability from both the indie side and corporate side.

“For a small studio, you need a ton of funding. You need to be able to fund whatever game you’re going to make. When you’re at a big company, it’s not so much that you need the actual dollars, because that’s why you’re at a big company, but you do need to build up that corporate karma, so that the leadership needs to be on good terms with everyone and be able to go out to drinks with whoever the CEO is or whoever the upper management is, and convince them that the product is going to be good,” she remarked.

“Also, there needs to be enough corporate karma to have a runway so that if we decide to cancel this game, because it’s not the right game, then we can keep going and make the next game… When I started at Zynga East, it felt like a really small startup because I started when we were six people in the basement of [industry veteran] Brian Reynolds’ house. But it was definitely like we’d have to go out every month to California and pitch or they’re going to, not only cancel the game, but probably just kill the studio. So, that was a pretty stressful time and definitely felt like a real startup.

“Then, when I was at Zynga in California, that was over 2000 people at the company, and we were trying to deal with all of the sliding puzzle pieces of teams coming together and pulling apart, and so that, I think, is also really helpful in my experience to share out.”

Assuming you’ve got the long-term planning down about what games to make at your studio, it’s then vital to make sure you have a steady flow of talent to grow from and the ability to keep your team together.

“Every summer, we bring in the top people from local universities, from Johns Hopkins, from University of Maryland, and we have good relationships with all of the professors,” Bell described. “[They] come in and do little consulting internships over the summer so that they get an idea of what we’re looking for, and it’s actually led to a really diverse pipeline of potential hires for us, and we do hire a lot of our interns. It’s so exciting to have these people coming in that just look more like America than the rest of the industry does, and it’s just great to work with a team like that.”

Bell’s a strong advocate for diversity and inclusivity, and while there’s no direct evidence that diversity directly ties into sustainability, we do know that diversity is good for business. And if business is good, odds are sustainability will follow.

“I think that it’s certainly more pleasant and more interesting to work on a more inclusive team, and so for that reason alone, we should do it,” Bell continued.

“Everybody should do it, everybody should try to build inclusive teams that have female programmers and people from various racial backgrounds. It just makes your games better, even if it’s two percent better because you have some characters, somewhere really far down the line in some quest that makes somebody happy, that’s important. It’s important to see yourself in games, and in media in general.”

Being able to keep your team together can sometimes be geographically dependent. While huge swathes of the industry are in California, cost of living and quality of life do matter. That’s why Bell is so high on Baltimore.

“One way [your team] can fall apart, of course, is if you run out of money, but another way is… just attrition, people just always spending two years with a company and jumping ship to the next company. That’s really, really common in the Bay Area,” Bell noted.

“What’s cool about having a company in Baltimore, is that, one, it’s a lot more affordable, but also, it’s a place where you make a life decision to move here and there are five or six studios in Baltimore, games studios, which all descended from MicroProse, in the early ’90s. But you come to Baltimore, you’re saying, ‘I’m pretty much going to be a part of this company and work for this company for the long haul,’ and that makes the team feel a lot different.

“I think you find this in other cities, as well, but if you’re in a place that’s not quite as busy, it does sort of keep your team together, and so we have people who, at the new Big Huge Games, who worked together at the old Big Huge Games, or even who worked together at Firaxis, back before Big Huge Games 1.0 was started.”

When people work together for 10 or 20 years at a time, there’s a stability to a company that tends to lead to sustainability. Of course, a key facet to keeping good employees around is to not burn them out. Crunch is still a persistent issue throughout the games industry, and Bell (an IGDA board member) had similar thoughts on the problem as IGDA Executive Director Jen MacLean.

“When I was Zynga and younger [I thought], ‘Whatever, I’ll work 60 to 70 hours in a week. We’re making tons of money, it’s totally worth it.’ But, now that I have a family it’s like, ‘Whoa, hold up, that might not be worth it.’

“So I definitely think part of my talk is focused on mid to senior level career people, because you hired these people, they’ve had a ton of skills and training in the industry, and then you don’t want to just lose them. We have such a problem with people leaving the industry, it’s important to think about that when you’re planning your production schedules,” Bell explained.

“I have two slides on crunch. One of them is about crunching with a purpose. It’s very important that you not crunch arbitrarily. My husband worked at a company that had their core hours from 9am to 7pm and that extra hour or two hours of crunch time, everyday, it adds up. There was no point to it. You know it was just like, ‘Well we’re in the video game industry. We’ll work hard,’ and so I think that when you do crunch, it’s important that it be a defined time and that it have a true purpose for what is needed for the game.

“And then the other thing that we’ve had a lot of success with at Big Huge, is that crunch … obviously, we try to avoid it at all costs, but letting people crunch from home, having all of that tech set up, so that people can VPN in from home and pull code and whatever. That, I think, makes it a lot easier for people with families to be able to hop on after dinner and be able to do some work from home.”

Bell added that it would be best to never crunch, but “despite everyone’s best planning, sometimes things come up, particularly, when you have a live game, that does need out of normal office hour work.”

In the end, this is where leadership skills are vital. Management must keep a close eye on working hours.

“I think that it’s important that management not reward the behavior of people who spend hours and hours at the office,” Bell said, “Because that often means that you’re not being as productive as you could be, during the time when everybody else is there. And I think that that’s something which definitely can cause problems when you have people who work really hard, within normal work hours and get a lot of stuff accomplished and it can be easy to fall into the trap of, ‘Oh but there’s this other person who stays until midnight, every night.’”

GameDaily.biz © 2025 | All Rights Reserved.

GameDaily.biz © 2025 | All Rights Reserved.