Subscriptions are becoming the dominant business model in entertainment, as the GameDaily staff discussed in our E3 2019 roundtable. Movies, TV and music have been overrun with them, and the game industry is not far behind, said Chris Early, Ubisoft’s VP of Partnerships and Revenue, during his Casual Connect London talk all about the rise of subscriptions in gaming. Before even diving into his presentation, Early made it clear that he’s “passionately against subscriptions, for the most part,” but he does understand the great value proposition it can offer some players.

Early began by noting that the games business faces a more complicated landscape than movies or music to begin with because there are platform-specific subscriptions as well as publisher or even game-specific subscriptions. For the platform, subscriptions are a great deal because they represent a predictable and consistent revenue stream while keeping players in a specific ecosystem.

“It’s much better to have an ongoing revenue stream than transactional revenue, even if it’s the same amount or if the transactional revenue is higher. That transactional revenue in our hit-driven business is just that, it can fluctuate,” Early warned.

For major publishers, the argument is similar but the big challenge is having enough content to satisfy the audience. “Unless you’re a publisher that has a significant breadth of content, the amount of content you’re going to bring on board is possibly going to be a challenge,” he said. “Having the variety or depth of content that people are going to want to subscribe for [can be tough].”

Subscriptions generally allow publisher or developers behind a specific game to reward loyal players. Ubisoft has done just that with its Just Dance Unlimited subscription. It’s a lot cheaper for players to subscribe than it would be to buy all the songs individually.

“The good news for us is we do make more money that way because we find people subscribe, and when they subscribe they consume more, and when they consume more they talk about it with their friends more, [so] it’s more engaging and it tends to spread overall,” Early explained.

From a purely economic standpoint, for a lot of players a subscription can pay for itself, assuming that the player would ordinarily buy a few games a year anyway. But for game creators? It’s a far more complicated picture and it may not be worth diving into the subscription fray for many.

It’s true that subscriptions can help with discoverability (especially if a platform chooses to feature your game), and subscriptions can open the door to hundreds of thousands, if not millions of players for a developer to tap into. But developers can’t necessarily rely on steady revenues for their catalog titles in a subscription service.

“Basically their message is just sit back, count the profits, put it in our subscription service and it will all be good,” Early said sarcastically. He went on to note that Ubisoft has tried putting games into subscription services on console a handful of times but has never seen much impact from the placement.

“We’re good at our catalog titles,” Early continued. “If you listen to our earnings reports, over half our revenue comes from our back catalog. We’re active all the time, our promotions work. We just find that even by offering someone big discounts, 70% off, we make more money than we get by being part of someone else’s subscription program. In a multi-developer content subscription, for us at least, we’ve got no control, we don’t own the message to the consumer, we don’t own when our content gets displayed, and there’s no consistency or predictability about our revenue stream.

“It’s very easy for someone to switch off and to try another game instead of continuing to play our game. And the games we design are hundreds of hours long… For someone to come in and in one or two sessions say, ‘Well I understand what this game is about’ and move on to the next, there’s no way we get the value out of it.”

It’s an interesting insight into Ubisoft’s mindset only one week before the French publisher would unveil its Uplay+ subscription during E3. The $14.99 per month service enables Ubisoft to control the message and the content. And if someone just wants to move on to the next game, as Early mentioned, it’s going to at least be another Ubisoft title.

Uplay+ will be offered as a publisher subscription on top of Google’s Stadia Pro as well. When someone in the audience asked about the value Ubisoft might see in Stadia, Early simply replied, “If we could make the same amount of money that we would make selling the game, I would love subscriptions. We just haven’t figured out how to do that yet.” Whether or not Early knew already about the Stadia deal is not clear, but he joked that, “My PR people would be very happy how I dodged that question, by the way.”

Of course, a giant company like Ubisoft can more easily navigate the choppy subscription waters than a small or midsize studio. For the average developer, adapting to a subscription model means considering three options: a development fee, a license fee or a straight revenue share. The development fee is a basic “work-for-hire” concept. A lot of the big platforms desire content, especially at launch, so they’re often willing to open the piggy bank.

Early said it can work for the right developer but cautioned that “after that [developer fee], there’s not much for you. There’s generally no ongoing revenue share, or very little, and you don’t own the IP in many cases. So you need to be happy with what you get as a development fee. That development fee is really all about that pitch and the team behind you. That’s how you can make sure you get the biggest fee possible.”

The license fee is another avenue to consider, but again, it has to make sense.

“It’s essentially an opportunity cost for you. The period of time that you’re going to be in the subscription offering is the period of time that people on that platform won’t be buying your product,” Early explained. “The more rights you give up, the higher the license fee will be. If you have the Game of Thrones license or the Westworld license, those are probably attractive to a platform’s subscription program. It gives them reasons, brings in new customers and it helps customers stay month after month.”

The third option, revenue sharing, isn’t particularly great for the average developer either. Essentially, all of the money paid by players for a subscription goes into a pool and developers then get a share of that pool based on the usage of their games, whether by hours (divided by total hours played by all games on the service) or by sessions days (divided by all games’ sessions).

Early broke down the calculations based on a $15 per month subscription for a service that offers 100 games (which is likely on the low end for major platforms). Assuming a traditional 70/30 revenue split would yield just $10.50 for developers. Even if every game is played equally on the service, the share would result in just 1% or 10 cents per player. That’s an incredibly difficult position for game creators to be in, and yet that’s the path that the industry is headed towards. This is the reality that many hard-working game developers will be (or already are) facing.

“Can you make money on 10 cents a player? I don’t know,” said Early. “That’s what you have to figure out… What if you put your game on sale for $5? You’d have to get 50 times more subscribers to pay for one guy who bought your game on sale. This is the problem that we have with this at Ubisoft. It doesn’t work out for us. Basically being average isn’t the way you win at the subscription game. You can’t just have an average amount of play.”

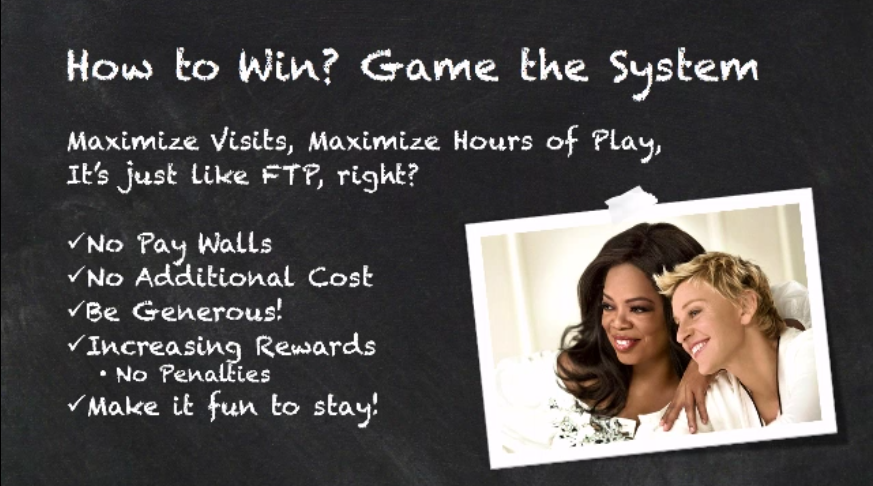

The repercussions of the subscription model will undoubtedly be felt by players too because developers will be effectively forced into trying out new tricks to monetize. The industry would be better off avoiding another loot box-style controversy, but Early outright suggested that developers tweak their designs to “game the system.”

“So how do you win?” he asked. “You now know how it is you get paid, so change the design of your game. Have it be more engaging, more hours, more visits, maximize the number of times people are there, the amount of time somebody’s there. These are somewhat free-to-play design mechanics, but they’re not. In F2P, would it be great to have someone turn on your game and leave it running while they went and did something else? Not really, but in subscription it would. Not that we would ever do that, right?”

Early’s advice is to “be generous” and rather than do something like limit the experience points earned after a time, reverse the mechanic so that players are rewarded for longer play.

“Every hour you’re there you double the amount of experience points you get,” he offered as a hypothetical design, before diving back into full-on sarcastic mode: “There’s probably some amount of time that you don’t want people sitting in front of the screen, but okay let them have the game running and keep accumulating those hours… uhh session days… uhh I mean experience points.

“So make it fun to stay. Basically what you want to do with your game is make it seem like the Ellen or Oprah show. Everybody’s screaming and they want to be there and everybody gets a prize.”

The newfangled subscription landscape is going to require game developers to adapt swiftly. Just as F2P ushered in new designs, so too will subscriptions.

“I think the only way we will figure it out is if we design for the business model. And if we design for the business model then we’ve got the chance to win,” said Early.

Casual Connect is now GameDaily Connect — stay tuned for more information on GameDaily Connect in Disneyland, August 27-29.

GameDaily.biz © 2025 | All Rights Reserved.

GameDaily.biz © 2025 | All Rights Reserved.