The World Health Organization (WHO) has drafted its 11th International Classification of Diseases and while it hasn’t been actively accepted by all member countries, the document is all but finalized. In it is a definition of a new disease classification: gaming disorder.

Gaming disorder is defined as: “A pattern of gaming behavior (‘digital-gaming’ or ‘video-gaming’) characterized by impaired control over gaming, increasing priority given to gaming over other activities to the extent that gaming takes precedence over other interests and daily activities, and continuation or escalation of gaming despite the occurrence of negative consequences.”

In order for this disorder to be officially diagnosed in a person, “the behavior pattern must be of sufficient severity to result in significant impairment in personal, family, social, educational, occupational or other important areas of functioning and would normally have been evident for at least 12 months.”

At the 15th annual Games For Change event in New York City, experts in the game industry, including a psychologist, sat down to discuss the WHO’s classification and how it impacts the industry at large. On the panel were Dr. Kelli Dunlap of iThrive Games, Lindsay Grace of American University Game Lab, Victoria van Voorhis of Second Avenue Learning, and moderator Jenn McNamara of BreakAway Games. Each of the panelists weighed in on the “gaming disorder” classification and what it means in their particular field of expertise in gaming psychology, design, or learning.

“Clinically speaking, one of the big controversies I think is that there are researchers and psychologists who believe gaming disorder is a thing and there are those who don’t,” Dr. Dunlap began. “[It’s] a gross oversimplification of the clinical process. All sides agree that you can play to an excessive extent. You can have problematic gaming. It is possible. The same way that you have problematic dance, the same way you could have problematic eating, the same way you could have problematic sleeping. Anything done in excess is not healthy. It’s kind of inherent to the term excessive, or too much.”

The academic divide is less about whether or not problematic gaming exists — it’s about the research that’s used to support the hypothesis.

“There are some researchers who say there’s not enough research to define gaming disorder as its own entity,” Dr. Dunlap admitted. “The research just isn’t there yet. We need more research so we can know what we’re looking for. The other side is basically saying, ‘It’s good enough where it is. There are people who are hurting, and if we have a disorder in place, one, it gives us a research target, and two, we can actually help the people who need help.’

“So that ultimately is the debate you’re hearing between academics. It is important to underscore that both people for gaming disorder and those who are opposed to its inclusion in the ICD-11 all agree that the criteria put forth by the WHO is too broad. So even people who support the disorder believe that the criteria is not good enough as-is.”

The broad strokes painted by the WHO in the ICD-11 point to the tip of the problem, rather than the problem itself, which is much more esoteric and not necessarily tied directly to gaming. It’s been pointed out before that game addiction is the manifestation of established DSM (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders) disorders or, in some cases, a comorbid psychiatric disorder.

“One of the things to note is that there are actually a large number of studies that call out the negative impacts of excessive television watching,” Dr. Dunlap said, “including aggression and obesity and a number of other cluster diagnoses, and those don’t manifest themselves in kids who game the same amount of time that people watch TV.”

Lindsay Grace, director at the American University Game Lab, weighed in on how games are a “misunderstood medium” and how that creates its own set of challenges. “[It’s] often [seen as] separate, where something like a television is ubiquitous. You see televisions in lots of living rooms, but you don’t necessarily see game consoles in those living rooms. I think that’s one of the reasons that people have such a hard time understanding [games].”

The overarching narrative with games and game addiction is one that paints a nefarious picture of game designers who deliberately “design for addiction.” To those working in design, however, lambasting creatives feels unfair. Jenn McNamara asked the panel if “designing for addiction” was really a thing that designers do.

“I haven’t met a designer yet who designs for addiction,” Grace said with a definitive edge to his voice. “I hope I never do. But we do design for engagement often and I think one of the strategies for engagement that makes a lot of sense is that we’re essentially trying to give people an opportunity to wholly invest in something.

“But, those experiences are often more rich when they are in comparison to the outside world, for example. So, players who participate in both the outside world and a game appreciate the experience, if it’s engaging. I think one of the odd, obvious problems with anyone who’s designing for addiction is the fact that you’re essentially looking to destroy your audience, which is probably not good.”

Victoria van Voorhis, CEO of Second Avenue Learning, talked candidly about how her company encourages designing for engagement, rather than for addiction.

“When you’re designing a learning game, you have discreet learning objectives that you’re designing for and very often those learning games need to be time-boxed, because they’re going to be used in either a formal or an informal educational setting,” van Voorhis responded. “So, you need to look for a play-through that might be 20 minutes or might occur over two or three hours of different sessions. And you have to design with that kind of intentionality.

“You’re looking for replay, but not beyond the need to get to mastery of what you want that person to take away from it. And so, the game itself is designed to get you in, make you learn something, and get you out and onto the next learning task. So that, in and of itself, creates a difference in the way you design.”

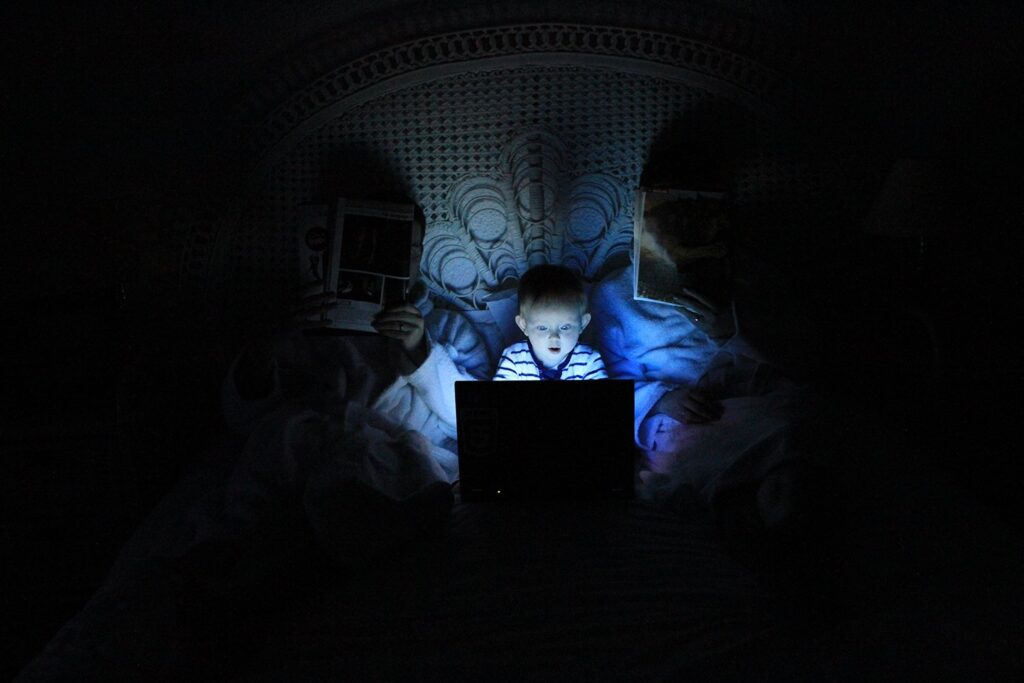

Engagement is a fickle thing. To some, engagement is still being aware of one’s surroundings and to others, full engagement is immersion, where the background fades away and all that remains is the entertainment medium, whether that’s a book, a movie, or a video game.

“When people observe people playing an entertainment game where they’re fully immersed and they’re actively engaged, almost to the point where they’re not engaging with the people around them, that can feel very scary to people,” van Voorhis continued. “It’s not the way people engage with other forms of media, except for maybe people watching a sports game on a Sunday afternoon in a bar or lounge, but maybe then they’re screaming at the television too.”

Conversations about addiction need to start with rudimentary knowledge of what addiction means. Psychology is still working to understand what behavioral addiction actually is, versus what we know about substance addiction. When a person experiences a drug, there are chemical changes in the brain that are produced as a result of the drug entering that person’s system. But behavioral addiction is a bit more esoteric. The studies surrounding behavioral addiction are less than 10 years old, which means that psychologists and academics are still working to define how it shows up in people with addictive tendencies.

“When you think about people who are addicts, we tend to think about people who are on really hard drugs, and really at the bottom of their life experience,” Dr. Dunlap commented. “You have people who are drunk driving, people who are passed out in the gutter, or whatever kind of trope you want to think about. So, tying that kind of label to an activity like gaming that is, for the vast, vast majority, 99% of players, completely normal and a healthy habit, is a little bit troubling for me.

“I also come from a psychological tradition that believes, very strongly, that addiction is something that happens when you put something into your body. So, there is a chemical change in your body, by putting a chemical in to your body. So the idea of behavioral addiction itself, I am less fond of, but I was totally off for that being my training, my background, and there are plenty of very wonderful psychologists who would disagree with me on that, and that’s fine.”

Even though behavioral addiction is still being explored as a concept, it doesn’t mean that there aren’t people suffering from games addiction.

In Asia, game addiction is a very real problem and has been for a number of years. Dr. Dunlap mused to the panel that this is potentially a reason why the WHO felt so strongly about introducing “gaming disorder” into the ICD-11.

“There was an open letter published by a lot of media scholars and psychologists that basically calls attention to gaming disorder and kind of called it out,” she noted. “They received a plethora of responses, about 14 different articles responding to their concerns, 10 of which came out of studies conducted in Asian countries. And the consistent tie-in with all of these studies is the researchers were very concerned because of the gaming camps and the detox camps that are a part of the treatment culture in countries like China and South Korea.”

She told a chilling story about what parents in Asia do if they discover their child has become addicted to games.

“If you haven’t heard about these camps, they are not summer camps,” she continued. “They are pretty much tantamount to child abuse and they, more or less, eat the gaming out of the children. And I mean that both literally and figuratively. So take that as you will. There’s evidence; it’s well documented, too. The idea that if we can medicalize gaming disorder, if we can make this practice for playing video games, if it is a medical condition, maybe parents and society will stop sending children to these kinds of really intense, inhumane camps.

“And so that is one of the arguments that is out there, one of the reasons there is a push for it. There’s a great new psychologist named Christopher Ferguson, who even wrote to one of the members on the WHO board who sent an overview of ICD-11 and that person stated to him — again this is hearsay — that they were receiving a lot of pressure for researchers in Asian countries to include gaming disorder because of these detox camps.”

Game addiction exists. And like chemical addictions, it hurts — it hurts families, friends, jobs, mental health, and it especially hurts the addict. The solution to the problem is going to require a lot more conversation than what we’ve been having, minus the internet discourse.

“I think the other way to solve this is to admit that we actually have a lot of unanswered questions,” Grace said simply. “It’s still a very young medium, and I think one of the challenges has been to start labeling behaviors in the community too soon, [which] may actually prevent the community from growing in healthy ways.”

Slapping labels on troubling behaviors is certainly one way to approach the issue, but it’s not necessarily the only one.

There’s nuance that many people tend to miss and it has everything to do with a combination of intent and societal judgment.

“Games are not inherently good or bad — they just are,” Dr. Dunlap said. “So I think you can be concerned. I have a two-year-old son and he loves his iPad and he has so many games on there and sometimes, even though I know all of the research, I worry, ‘He’s had too much screen time today.’ I think it’s totally fine to be concerned. I think as humans, especially as parents, being concerned about people we care about is a good thing.”

That’s why the WHO has felt pressure to define and label the addiction as a disorder: concern and caring. The people that are affected by video game addiction are usually the addict’s family and friends. They have no real control. They want to do right by their loved one, but without the resources to get their loved one some semblance of help for their addiction, they feel powerless. They want the pain to stop and they need it to stop now, which is likely how the Asian gaming detox camps started up. No one on the panel denied that there were issues that needed to be addressed.

“One thing I think is really important, at least [on] the clinical research side, is everybody is trying to do right by the players,” Dr. Dunlap reassured the panel and the audience. “Nobody wants anybody to suffer. And right now the division really comes from, ‘How can we best help people that are in need of help?’ And so I really don’t even see that much as a division within the psych space, though I think that it is portrayed that way oftentimes. It’s important to be mindful and aware of the negative side of things, but it’s important not to focus on that exclusively. That becomes fear mongering. We don’t want that.”

Video game moral panic is nothing new, but it is insidious. Hopefully, with nuanced discussions and better research, those afflicted by addiction to games will be able to get the help that they need without making it harder for the game industry to do what they do best: entertain us.

GameDaily.biz © 2025 | All Rights Reserved.

GameDaily.biz © 2025 | All Rights Reserved.