This is summarized from McMillan LLP’s Business Law Bulletin and white paper published here.

Video games have become a massive business. In 2018, interactive media revenues grew to reach USD$119.6 billion (+13%), vastly more than the global recorded music industry at USD$19 billion (+9.7%) and rapidly approaching the global film industry at USD$135.6 billion (+2.5%). With competition for consumers’ entertainment time at a fever pitch across converging industries—including, famously, Netflix who consider Fortnite as a bigger competitor than HBO—game developers are under immense pressure to deliver immersive, compelling, perfectly-executed games that take full advantage of the latest technology. Game development costs to deliver these high-fidelity games have increased by an order of magnitude (even ignoring increasing marketing spends), but retail prices for AAA console and PC games have remained relatively stagnant, drastically decreasing when taking into account inflation.

These pressures, combined with increased global competition and an ever-saturating online storefront ecosystem, have driven developers and publishers to seek alternative business models and creative revenue streams to remain profitable, such as “free-to-play”, microtransaction, ad revenue and subscription models, and sometimes mixes of those. With a confluence of three factors—the amount of revenue being generated in virtual, in-game economies; the existing media, political and sometimes parental bias against video games (both in terms of utility as well as in terms of appropriateness for children); and a controversial (and scientifically dubious) decision by the World Health Organization to classify “gaming order” as a disease—it is no surprise that in-game business practices have come under the close scrutiny of regulators and consumer organizations around the world, to varying degrees of success.

Against that backdrop, regulation like that proposed by Republican Senator Josh Hawley’s new billshould come as no surprise—even if the sledgehammer approach of the bill itself to the entire interactive entertainment industry is shocking. The legislation purports to “regulate” pay-to-win microtransactions and loot boxes, but in doing so would actually would make it illegal to make available any game containing pay-to-win microtransactions or loot boxes if the game a “minor-oriented video game”, or even in other games where the publisher or distributor has “constructive knowledge that any of its users are under the age of 18”.

While moving far beyond regulation and unnecessarily into prohibition, the “minor-oriented video game” prohibitions of the bill may not, themselves, represent a true industry earthquake—despite popular impression, game economies generally do not target games at children as they are not as likely as adults to stick with a game (and tend to head to the most recent or popular game), and they do not spend as much money adults, whose greater disposable income and brand loyalty make them a much more attractive audience. (In fact, one wonders whether it would shock Senator Hawley, himself not a gamer, that the average gamer is 34 years old with adult women representing a nearly bigger portion of the game-playing population than boys under 18.)

Instead, the bill’s stretch to prohibit any game that could be played by minors, and its broad definition of “pay to win”, should give gamers and game companies serious pause. And by that, we mean the adult game players, not the children.

Popular games will always be played by minors. A NewZoo study found that two popular games (Epic’s Fortnite and Bluehole’s PUBG, both of which heavily feature microtransactions) had majority player populations between the ages of 10 and 30, with between 10 and 20 percent of players identified as “students”. Furthermore, the bill’s definition of a “pay-to-win” transaction is incredibly broad, focusing on progression through the game by easing progress, assisting achievements, or obtaining or elongating access to awards that might otherwise taken be away—in each case even if these can be done without purchase.

Short of very intrusive age verification techniques, game companies would be put in a position of not being able to offer the game if they know children play, or removing elements of games that players (through their economic voices, i.e. their wallets) have clearly enjoyed. One strains to imagine another adult-oriented businesses where there is a prohibition from running the business where it is constructively known that minors actually participate despite efforts to prevent it.

As such, the bill is very broad in its reach, perhaps to a point where a court would not find it enforceable and certainly to the point where both gamers (who want entertaining, high-production-value products) and game companies (who want to make money) should be shocked by its approach. The industry itself is indeed vocally opposed to this type of regulation (as one would suspect), we note that in our observations of online discussions about this bill, reactions from game players themselves are as clear-cut in opposition, with many players feeling that games have, indeed, gone too far with monetization efforts. So there is a kernel of truth to the bill’s purpose, and perhaps one that is worthy of regulation.

The games industry has resided in a protective bubble: largely ignored by regulators, protected by US courts on First Amendment bases, benefitting from the ubiquity and transborder reach of (and difficulties of governance brought by) the Internet, and treated as “kid’s stuff” and not the massive, Hollywood-beating industry it has become. Within that protective bubble, those making money from video games have started to act as if they could not be regulated in the same way that other industries and businesses have been regulated. This may come as a result of some unwarranted confidence from consistent, early court wins. As video games became more realistic, attempts at regulating their mature content failed.

In the landmark U.S. case of Brown v. Entertainment Merchants Assn, the Supreme Court ruled that video games qualify for First Amendment protection like “books, plays and movies” through traditional devices but also features only electronic entertainment could provide “such as the player’s interaction with the virtual world”, and that the California government had not met its burden of balancing that protection with its regulatory attempts. Regulation for content in other jurisdictions has fared better (notably, for example, China and Germany), but it generally took some time before the worldwide regulatory focus shifted from the content of games to the economics of games.

Different jurisdictions have looked intermittently at game economies and gamer behavior, not just at the content. Japan and Korea have regulated certain gambling-like mechanics or compulsive gaming hours. The European Commission has opined on the marketing of “free-to-play” games. Several jurisdictions throughout Europe, Asia and even North America have taken an interest in loot boxes, focusing on gambling, child protection, consumer and even money-laundering.

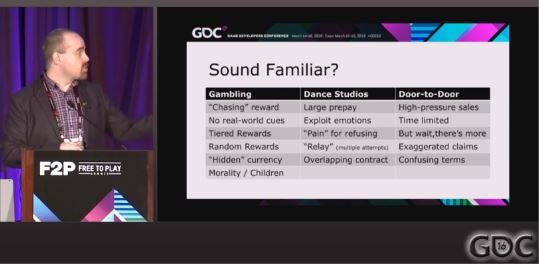

Even ignoring the obvious regulatory oversight that would come with a gambling analogy, we can clearly see examples in other industries of behaviours that we see in games that have been deemed worthy of regulation worldwide. High pressure tactics, exploiting consumer weakness, playing on time sinks or up-front investments, confusing contracts/terms, unknown or not clearly represented rewards and other similar factors have caused governments to regulate everything from dance studios to door-to-door salespeople. At a 2016 presentation at GDC, I pointed out that the rationales behind regulating behaviours in those industries are quite familiar to anyone who has played a modern game, particularly one that relies heavily on microtransactions:

So an effective type of regulation would not focus on the artistic value or content of the game itself, but the transactions and behaviors conducted through the games. There is little doubt that many of today’s interactive games rely on mechanisms common in regulated industries and known to encourage (and sometimes exploit) consumer spend, including:

Combined with the scientific research that shows that the frontal lobe, the part of the human brain responsible for executive functions, resisting urges and decision-making, does not fully develop until approximately 24 years of age, it is apparent why regulation, particularly when purporting to focus on young people, is attractive to governments and may in fact gain traction.

In the video game industry, self-regulation has been effective, not just in staving off legislation, but actually preventing children from accessing inappropriate content. In 1994, the Entertainment Software Ratings Board (ESRB) was established to administer “a rating system [that] should inform and suggest, not prohibit” games, after Senate hearings focused on mature games such as Mortal Kombat and Night Trap, and provides the well-known information labels on game conduct. The ESRB ratings system were an instrumental part of the California government’s defeat in the Brown case mentioned above, with the US Supreme Court stating:

[…] California cannot show that the Act’s restrictions meet a substantial need of parents […] In 2009, the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) found that, as a result of this system, “the video game industry outpaces the movie and music industries” […] This system does much to ensure that minors cannot purchase seriously violent games on their own, and that parents who care about the matter can readily evaluate the games their children bring home. […] [Emphasis ours.]

With today’s gaming ecosystem, there are some inherent weaknesses in the ESRB ratings model that are becoming exposed, such as the fact that most games are not sold or marketed physically anymore but instead via online stores where consumers don’t have much opportunity to see these labels or parents to review them. But the ESRB and other bodies like it have shown that self-regulation, or even government-mandated regulation (as opposed to prohibition) can work. I and others have long advocated for the interactive entertainment industry to rally around a set of ethical monetization principles, which could be (and often, are) enforced by industry leaders, self-regulatory bodies or even the government sparingly, including:

Whether this bill advances, or stands a chance politically or under judicial scrutiny, is a matter for my American colleagues to discuss and perhaps litigate, but clearly the push for regulation such as this bill will be appealing to politicians. The message will heavily focus on childrens’ perceived exploitation: a big difference between video games and other forms of entertainment is that a significant portion of the population and politicians will have a negative attitude towards gaming on moralistic, paternalistic or other grounds. And so, much like the attempts to regulate games in the past for encouraging violent behaviour in children (when studies do not show any actual effect worth tackling), the “protect the children” tactic, combined with a dose of consumer protection, has clearly emerged as the preferred rationale for this type of business activity, particularly in the United States with its strong First Amendment protections.

Clearly, the regulatory bubble has been burst, and game companies must take seriously the concepts of self-regulation, meaningful parental controls, monetization restraint and consumer deference if they want to avoid the worst of it from governments around the world.

The foregoing provides only an overview and does not constitute legal advice. Readers are cautioned against making any decisions based on this material alone. Rather, specific legal advice should be obtained. This article contains the authors’ opinions and not McMillan LLP’s. This article also features contribution from Tyson Gratton; Associate, Business Law; and Colin Cheng; Associate, Capital Markets.

GameDaily.biz © 2025 | All Rights Reserved.

GameDaily.biz © 2025 | All Rights Reserved.