Jason Roberts is not your prototypical game developer. He’s new to the scene, but he’s in his 40s. He didn’t go to design school or team up with his buddies to work on a project from his basement or garage. He quit his job as a software engineer in 2012 to pursue his vision. And for the most part, the bulk of Gorogoa was created by Roberts himself.

“I had been designing games kind of in my head since I was a teenager, I think,” he told GameDaily. “But they never seemed [like they would work out], the designs never seemed too practical. I didn’t think it was possible for one person to make a game. I didn’t want to go through the whole career path, career grind, of working for a big game company.”

As Roberts noted, when he decided to start working on Gorogoa in 2012, the marketplace was different than it is now. Discoverability hadn’t quite taken a turn for the worse yet, and the indie renaissance was in full effect, as numerous developers gained inspiration from Jonathan Blow’s Braid (among others).

“I think it was when Braid came out, that made a big impression on me [and] a lot of people,” Roberts said. “It was a successful game, and it was made by a very small number of people, and I didn’t even think of that as possible. That proved that something [artistic] could be done … I had long wanted to make a game, and I also wanted to make a visual art project. I just wanted to make a big project that had lots of colorful drawings that I could do, so I was as much motivated by desire to do a big art project as I was to make a game, and then found a way to make those two things synergize.”

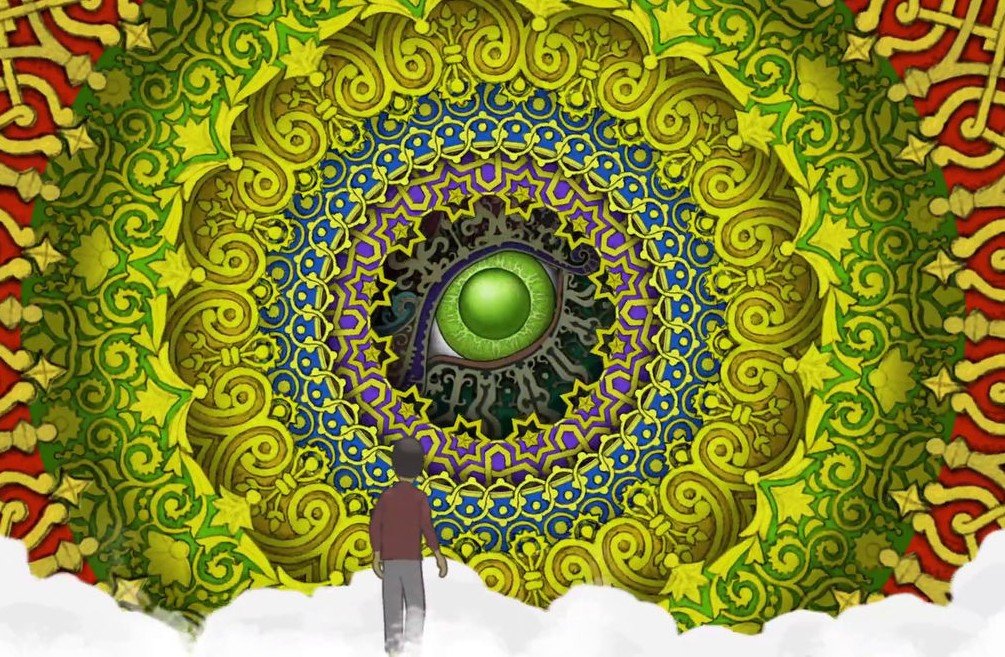

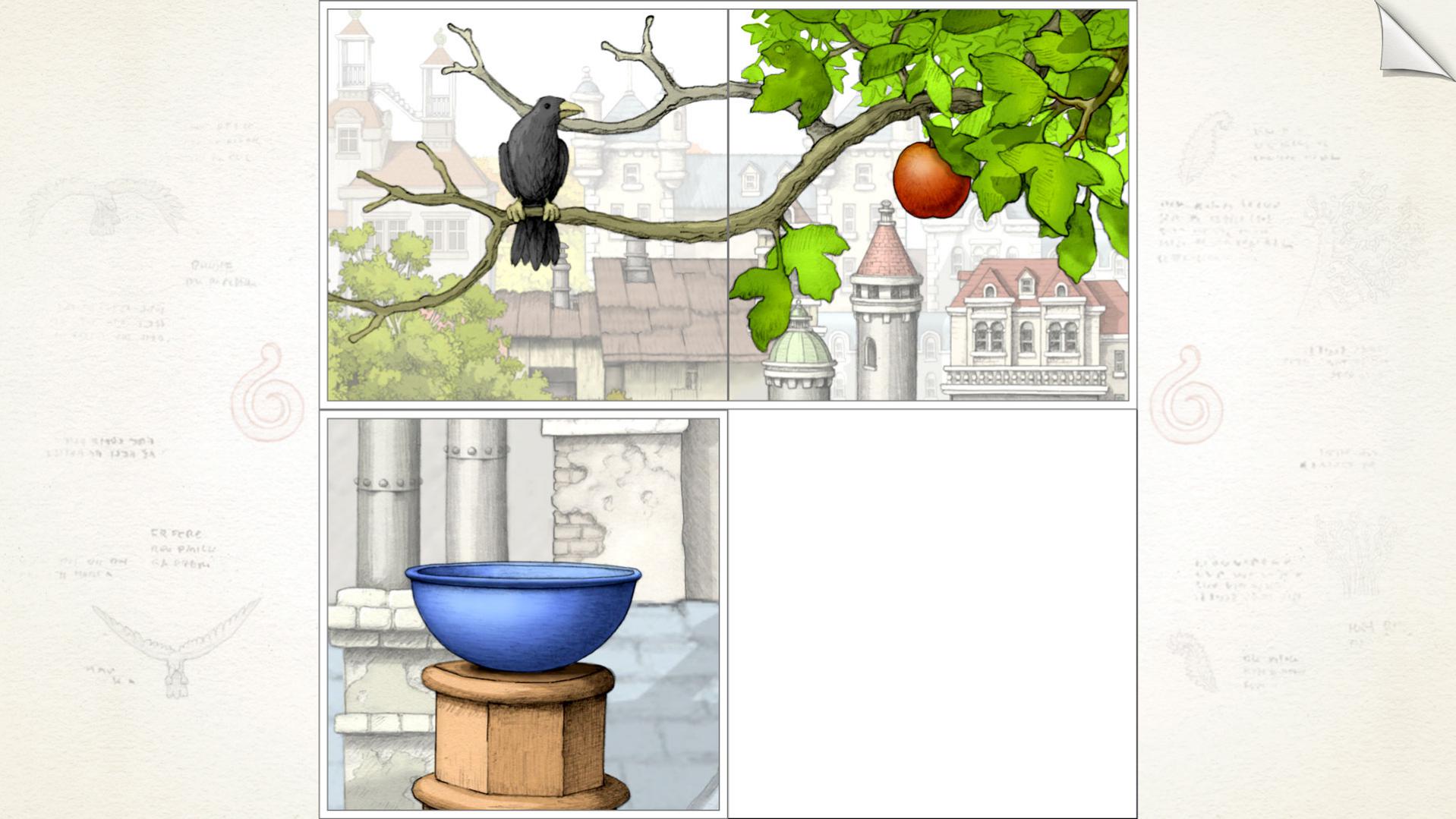

Gorogoa, on the surface, is merely a puzzle game. The player moves around and stacks tiles of hand drawn art (clearly inspired by comics and graphic novels) and those actions then result in certain animations taking place to tell a story. It’s a narrative without any dialogue, similar to fellow Annapurna Interactive published title Florence from Ken Wong.

As the player gets deeper into Gorogoa — quite literally, as the game has you factoring in the Z axis as well — the veneer of the puzzle mechanic is eroded so that the meaning of the game becomes clearer. It’s about the nature of life, of the world, and the entire cosmos as a whole. Roberts wants us all to examine the duality of, well, everything.

“I’m thinking of looking at the solid, everyday world, and seeing another sort of reality, or something larger, something invisible, and eternal, or magical, superimposed on that,” said Roberts.

“In the game, that other world is represented by this mysterious creature, and a character’s kind of yearning to find his way to that invisible world. So it’s, I think, more about duality, and the nature of the world and in people.”

There are a number of scientists, including the late physicist Stephen Hawking, who’ve entertained the idea of a multiverse. I couldn’t help but wonder if this idea of dualities and other realities was in part inspired by this hypothesis.

“I wasn’t specifically thinking about that, but I see how it resonates,” Roberts remarked. “It’s the desire to feel like you’re part of a larger pattern than what you can see. And I think that’s a theme that I will carry forward into future projects, just because it’s something that is compelling to me, kind of like taking the everyday world, and then looking at it from a different perspective, an outside perspective, so that you can see the larger, and hopefully beautiful, structure that it’s a part of.

“And that is compelling, and comforting, as a concept. Whether or not we might struggle to actually believe it in reality… I’m drawn to that, and that informs my design decisions. And it sort of has to be mysterious, that larger structure.”

Human beings, especially those approaching mid-life, often ponder their own mortality and the meanings of their lives. This thought process is naturally intensified if you’ve recently lost a parent or loved one. As it turns out, I and Roberts both lost our fathers in the same year. And while Roberts lost his dad when work on Gorogoa was all but completed, he acknowledged the importance of questioning mortality in his approach.

“I think that mortality is why you have these thoughts,” he said. “I think [my inspiration for Gorogoa] had to do with kind of drifting away from religious faith as I grew older, but still having that echo of wanting something to be there, that is beyond what’s visible. Or to believe that there’s some kind of purpose, or authorship, in the world around us, in the world that we live in. And it’s not that I actually feel that that’s the case, it’s more like a fond memory. So, it’s kind of a wistful dream, at this point.

“The specifics of the religious faith I was brought up in didn’t connect with me, really. So that’s why … in some way, maybe specific details of those religious traditions is the problem. I’m more drawn to ideas of faith that are more mysterious, because anything that is unknowable is more [resonant]. If I imagine that there’s something else out there, it has to be incomprehensible, so if it can be described in a book, then it’s too limiting.”

Considering that Gorogoa was Roberts’ first game, he’s made quite the impression, earning the praise of critics and gaining a number of awards, including a BAFTA for best debut game.

“It’s been very gratifying,” Roberts commented. “It took a long time. It took enough time that it could’ve been my third game. I sort of just rolled the first two games, first two short, throwaway games worth of learning into this project. So it is my first game, but it’s like having five years to work on it is what allowed me to get away with that, I think. That was never the plan, of course.”

Creating Gorogoa was very much a learning process, and not just about game development but about Roberts’ ability to accept his own limitations.

“It’s been a process of letting go,” Roberts acknowledged. “At one point I wanted to try to do all my own sound design, very early on. And I eventually said, ‘This is not my area of expertise, and I’ll collaborate with a sound designer,’ and now I have that feeling about animation. And it was so time consuming for me, because I didn’t know what I was doing. So work with an animator. I guess that’s one sort of regret, one thing I might consider doing differently, if I had it to do over again.

“I’d say the animator is like an actor, in that they’re creating a performance, and I was doing my own animation. It was like being a director and casting myself. And then just writing the story around my own limitations.”

“I [also] learned not to finish the expensive pencil art too soon. So if I could go back and tell myself something, I’d be like, ‘Look, just do design scenes in the simplest version of the art that still captures the visual idea, and then do the pencil art for everything dead last.’ So, that was a learning experience.”

Designing puzzle elements with tiles on a 2D plane that also factored in 3D space was one of the hardest parts of making Gorogoa, according to Roberts. It all needs to come together just right and without being overly difficult for the player to both understand and interact with.

“That was super [hard]… getting things to align spatially and visually in a scene that is at least pretending to be a 3D space was challenging, and I would start out aligning things from one perspective, and then I’d find the point of view from which two tiles need to connect together, and then sort of build the scene backwards from there,” Roberts explained.

“It was still a huge amount of trial and error, and just making art, throwing stuff out… everything I made felt like sort of a simple idea in some ways. But then, actually making two things visually fit together, and then also look plausible within the scene, and from different vantage points like that, it just took so much sitting down and trying one shape, and then trying different colors … so it’s not as much of a formalized process, it’s just kind of wiggling and nudging things back and forth until they feel right.”

For some developers, a perfectionist mindset takes hold. They might already have a very good product on their hands, but they are unwilling to release the game into the wild. Game design is an iterative process, after all, so it can be hard to know when to stop iterating. That said, Roberts insists that Gorogoa needed the extra time.

“I’ve been accused of being a perfectionist, but I don’t think that’s the case. I think the design of the game had serious issues with it, up until half a year before release,” he stated. “I think had I been forced to release it a year earlier, it’s not just that it would’ve dissatisfied me, because it has a few unpolished corners, I think the reception would’ve been not nearly as good, because people would’ve been bummed by the difficulty curve. I think it rides a fine line between being too challenging for some people or being too obscure for other people, and so to thread that needle took a lot of work, and it wasn’t like 95% as good, a year ago. It was half as good… just in terms of working as a game, and as an experience, it needed that much time, because as I say, I was learning. I was figuring stuff out as I went along.”

Now that Roberts has been fully indoctrinated into the game development scene, he’s encouraged by the creativity and artistry of his peers and what the medium of games can offer, but he’s also keenly aware of how hard it’s become for some developers.

“As a medium, I’m very optimistic,” he said. “I haven’t been able to play as many games as I wanted in 2017, so I’ve got a big backlog, but there are amazing [games to choose from]. Games are as vibrant, thematically, aesthetically, mechanically diverse, I think, as they’ve ever been. At least in the indie world.

“And I think it’s becoming harder to describe the prototypical indie game, and that’s great. It’s a new medium, people are still figuring out how to use interactive mechanics to be expressive. Florence, from Mountains, is a great example of that, of just using the mechanics very, very craftily, and confidently to tell a story. The fact that games have the freedom to do that kind of thing now is very encouraging, and again, I sort of see mostly the indie world, and it’s a different landscape, different economics for bigger games.

“But the market is still very challenging for a lot of indie games. A lot of games that seem like they should have been successful don’t find an audience. It’s harder to get people’s attention, and that doesn’t seem likely to change. It’s encouraging the so called ‘indiepocalypse’…hasn’t seemed to throttle the number of interesting games out there.”

Some would believe that the cream always rises to the top, but that’s not guaranteed when you have thousands upon thousands of titles on digital storefronts. Luckily for Roberts, Gorogoa had the publishing assistance of Annapurna Interactive, but some indies choose to go it alone and that can be very risky.

“Some games end up having a hook that gets people’s attention, and is good at generating word of mouth. That’s a quality that many good games have, but not every good game has that hookiness, or even the right kind of hookiness, at this particular moment in history to create a groundswell of interest. So I don’t know that all the cream is rising to the top. It has to be exactly the right flavor cream for people’s taste at the moment,” Roberts added.

With Gorogoa having landed on mobile, PC and Switch last December, Roberts has already turned his attention to what he’d like to create next. The vision isn’t fully formed, but he does know that the concept of tiles is something he wants to explore further.

“If you think about Gorogoa, it’s difficult to pitch, or describe how it works. Especially if there’s [nothing to show]. I want to get to the point of building a prototype, so I can show people,” he said. “I think I can build a simple example, and then show it. Maybe I’ll have something next year… In a way it’s a conceptual relative of Gorogoa, in that it has scenes inside of panels, because I’m still interested in that, but the way they interact is much more elaborate, and different than Gorogoa.

“So I’m continuing to explore what I consider to be a space with a lot of potential, which is these multi-panel or multi-frame games, which I think should be a genre of games; it’s not just a single, or small set of games. It’s about how images and stories and scenes interact with each other, across this sort of in between space, and that’s what I want to explore.”

GameDaily.biz © 2025 | All Rights Reserved.

GameDaily.biz © 2025 | All Rights Reserved.